Conflitos no local de trabalho são uma parte indesejada, mas inevitável, da experiência de trabalho. Onde quer que haja pessoas trabalhando juntas, mais cedo ou mais tarde haverá desentendimentos. É aí que a resolução de conflitos entra em jogo. Ou seja, a resolução de conflitos em equipes é o processo que os colegas de trabalho usam para encontrar uma solução amigável para um problema no local de trabalho.

Por razões óbvias, essa área de esforço profissional tem sido objeto de várias pesquisas. Há uma variedade de teorias e soluções propostas para a resolução de conflitos no local de trabalho, mas uma coisa fundamental é universalmente aceita: a questão não é como prevenir o conflito, mas como abordá-lo quando ele ocorre. Na verdade, alguns especialistas até veem o conflito como positivo, uma oportunidade de tornar as equipes mais coesas e produtivas.

Nas linhas a seguir, examinaremos como e por que os conflitos no local de trabalho ocorrem, como identificar adequadamente as situações conflitantes e resolvê-las de maneiras que não comprometam o trabalho da equipe.

A resolução de conflitos não é uma técnica uniforme de pintar por números. A maneira como abordamos o conflito depende muito do contexto — qual é a causa do desacordo, quem são as partes envolvidas, quais são suas características pessoais, etc. Portanto, para abordar adequadamente a situação, precisamos primeiro entendê-la.

Vamos dar uma olhada nos tipos mais comuns de conflitos no local de trabalho.

Tipos de conflitos no local de trabalho

O conflito organizacional pode ser definido como um desacordo ou oposição a interesses ou ideias. Conflitos no local de trabalho surgem de diversas formas, mas podem ser classificados em duas categorias: substantivos ou emocionais.

Conflitos substantivos

Conflitos substantivos ocorrem quando as partes envolvidas discordam sobre questões estratégicas ou operacionais — metas, ações para atingir essas metas, alocação de recursos, etc. Por exemplo, membros da equipe discordando sobre a estratégia de marketing para o lançamento de um novo produto ou sobre a introdução de um novo software que alguns podem considerar disruptivo ou desnecessário seriam considerados conflitos substantivos. Esse tipo, em comparação com os conflitos emocionais, é mais propenso a gerar um resultado positivo, pois está enraizado em questões racionais e práticas, com um componente emocional muito menos enfatizado.

Conflitos emocionais

Conflitos emocionais são desacordos interpessoais que decorrem de emoções negativas, como raiva, medo, desconfiança, antipatia, ressentimento e assim por diante. Embora a natureza e a causa do conflito possam ou não ser explicitamente declaradas, todos os conflitos emocionais carregam uma nota de animosidade pessoal de pelo menos um dos participantes.

O que causa conflito?

As causas dos conflitos no local de trabalho são tão numerosas e diversas que é difícil tentar encapsulá-las completamente. No entanto, destacaremos várias das raízes mais comuns de desentendimentos no local de trabalho.

Adversidade

Tempos de dificuldade (econômica ou não) são uma grande causa de estresse, o que pode levar muitos membros da equipe ao conflito. Por outro lado, tempos difíceis também podem aproximar os membros da equipe, e conflitos em tempos de adversidade podem se transformar em oportunidades para aumentar a coesão da equipe.

Recursos limitados

Uma das causas mais comuns — no local de trabalho e além — é o desejo pela proverbial fatia do bolo. Se essa fatia não pode ser compartilhada entre aqueles que aspiram a ele (por exemplo, uma posição de liderança), isso pode facilmente resultar em conflito.

Comunicação ruim

Os conflitos no local de trabalho geralmente surgem de mal-entendidos decorrentes de habilidades de comunicação defeituosas. Algo que é dito pode ser mal interpretado, e algo não dito pode ser tomado como hostilidade. Uma vasta experiência revelou uma correlação bastante direta entre habilidades de comunicação subdesenvolvidas e a probabilidade de se envolver em conflito.

Preconceito

As diferenças percebidas com base em nação, raça, religião, sexo, classe, sistemas de crenças ou quaisquer preferências gerais são uma causa comum de conflito (e, no caso oposto, uma causa comum de alianças). Quanto mais nos opomos ao que uma pessoa representa, mais provável é que nos oponhamos às suas ações específicas no local de trabalho.

Ambiente

Fatores ambientais como calor, umidade, barulho ou cheiros podem criar e/ou aumentar estados emocionais negativos, predispondo assim os membros da equipe a conflitos.

Saúde

Doenças e cansaço geral, assim como quaisquer outros estados físicos abaixo do ideal, podem diminuir significativamente nossa tolerância, levando a estados elevados de agitação que podem facilmente se transformar em conflito aberto.

O conflito pode ser algo positivo?

Embora possamos presumir intuitivamente que o conflito vai contra os valores do trabalho em equipe, e da colaboração, esse pode não ser necessariamente o caso. Na verdade, evitar o conflito em prol da diplomacia e da manutenção de uma aparência de harmonia levará quase inevitavelmente a um conflito maior no futuro. Deixar de reconhecer e abordar um conflito não o fará desaparecer — apenas adiará e potencialmente alimentará o seu tamanho.

Por outro lado, abordar o conflito de maneira respeitosa e construtiva pode produzir benefícios significativos para a equipe como um todo. Alguns desses benefícios incluem:

- Liberação de pressão e frustração;

- Maior compreensão dos outros e de nós mesmos;

- Melhoria na tomada de decisões e na capacidade de resolução de problemas;

- Maior coesão da equipe;

- Minimização da complacência;

- Apreciação das diferenças;

- Introdução de mudanças.

Como resolver conflitos no local de trabalho

Como estabelecemos, há muitos tipos, causas e contextos diferentes de conflitos no local de trabalho. Se quisermos abordar a resolução de conflitos da maneira mais otimizada, não podemos utilizar a mesma abordagem para todas as situações. Em vez disso, precisamos entender a situação da melhor maneira possível e ajustar nossa abordagem de acordo.

Indivíduos que tentam chegar a uma resolução positiva de um conflito podem escolher realizar uma série de ações (ou omissões) para atingir esse objetivo. Essas ações são:

- Evasão de ação: deixar as coisas acalmarem com o tempo, bem como ignorar insultos ou ameaças;

- Retirada: “sair da mesa”;

- Dominação: afirmar poder sobre outras partes envolvidas;

- Capitulação: ceder ao outro lado;

- Jogo de poder unilateral: recorrer à violência, desobediência ou intriga;

- Encaminhamento para a cadeia de comando: envolver a alta gerência;

- Negociação: tentar chegar a um acordo por meio de compromisso e encontrar um ponto comum;

- Mediação: envolver um terceiro em uma capacidade consultiva;

- Arbitragem: envolver um terceiro com poderes de tomada de decisão;

- Litígio: procedimentos judiciais.

As ações acima mencionadas são “ferramentas” que constituem diferentes estilos de gerenciamento de conflitos que podem ser utilizados dependendo das circunstâncias específicas. Vamos dar uma olhada nos estilos de gerenciamento de conflitos mais comuns e avaliar as situações para as quais eles são mais adequados.

Estilos de gerenciamento de conflitos

Os renomados analistas de conflitos Kenneth Thomas e Ralph Kilmann desenvolveram um modelo que identifica cinco estilos específicos de gerenciamento de conflitos:

- Competindo;

- Colaborando;

- Comprometendo;

- Evitando;

- Acomodando.

O modelo Thomas-Killman é baseado em combinações de comportamento assertivo/não assertivo e cooperativo/não cooperativo, onde o primeiro indica a intenção de uma parte de satisfazer suas próprias preocupações, e o último sua intenção de satisfazer as preocupações dos outros. Nenhum dos estilos é inerentemente melhor do que os outros; em vez disso, todos eles podem ser usados dependendo da situação específica em questão. Por outro lado, os autores acreditam que todos são naturalmente inclinados a um dos cinco estilos, e é por isso que é importante entender os benefícios de cada estilo e tentar ajustar nossa abordagem para melhor abordar qualquer situação específica.

Vamos dar uma olhada mais de perto em cada um dos cinco estilos de gerenciamento de conflitos.

Competindo

Buscar ativamente um resultado benéfico para o seu lado do argumento. Este estilo é mais adequado para as seguintes situações:

- Em situações de emergência onde uma ação rápida e decisiva é de extrema importância;

- Em questões relevantes envolvendo decisões impopulares (por exemplo, disciplina, corte de custos, etc.);

- Em questões que são vitais para o sucesso de uma empresa onde você tem absoluta certeza de que está certo;

- Em disputas com indivíduos que prosperam com o comportamento não competitivo de outros.

Colaboração

Uma abordagem que visa criar uma situação mutualmente favorável por meio de um esforço conjunto das partes envolvidas. É recomendável para as seguintes situações:

- Quando ambos os lados têm preocupações que são importantes demais para serem comprometidas e onde uma solução integrativa é necessária;

- Quando o aprendizado é o objetivo;

- Quando desejamos fundir perspectivas divergentes;

- Quando desejamos obter comprometimento mútuo ao atingir consenso;

- Quando precisamos expor sentimentos que impedem um relacionamento de trabalho.

Comprometendo

Tentando encontrar a outra parte no meio do caminho. Essa abordagem é mais adequada para situações em que:

- As preocupações e objetivos não são importantes o suficiente para potencialmente ameaçar questões mais urgentes;

- Oponentes com poder igual estão comprometidos com objetivos mutuamente exclusivos;

- Uma solução temporária de questões complexas é necessária;

- Uma solução rápida é necessária sob restrições de tempo;

- Colaboração ou competição não são bem-sucedidas.

Evitando

Ignorar o conflito e não se envolver em nenhuma discussão. Essa abordagem raramente é recomendável, mas pode ser utilizada nas seguintes situações:

- Quando um problema é trivial e há preocupações mais urgentes;

- Quando não parece haver uma chance de satisfazer nossas preocupações;

- Quando a potencial interrupção supera os benefícios;

- Quando é mais importante reunir informações do que chegar a uma decisão;

- Quando um conflito pode ser resolvido com mais sucesso por outros;

- Quando o problema em questão é uma manifestação de um problema subjacente maior.

Acomodando

Ceder a “vitória” à outra parte. Este estilo é particularmente eficaz nas seguintes situações:

- Quando percebemos que estamos errados;

- Quando desejamos criar uma posição melhor para sermos ouvidos, aprender e mostrar que somos razoáveis;

- Quando as questões são mais importantes para os outros do que para nós mesmos;

- Quando desejamos ganhar crédito social para benefício futuro;

- Quando devemos cortar as perdas;

- Quando a harmonia é mais importante do que atingir nosso objetivo;

- Quando desejamos permitir que outros aprendam com os erros.

Para reiterar, nenhum estilo é superior a qualquer outro e devemos fazer o nosso melhor para avaliar adequadamente a natureza e o contexto do conflito antes de decidir uma direção.

Quem deve gerenciar o conflito?

O senso comum sugere que o gerenciamento de conflitos deve ser deixado para os gerentes (líderes de equipe, coordenadores, chefes, etc.), mas esse nunca é o melhor cenário. Esse tipo de solução de problemas não inclui necessariamente uma abordagem de cima para baixo, e os gerentes não devem intervir em todas as disputas.

O ideal é que os membros da equipe em disputa consigam resolver o conflito eles mesmos. A intervenção de terceiros apenas dificulta a colaboração e aumenta a dependência da equipe de um gerente. Em vez disso, os gerentes devem trabalhar para permitir que os funcionários resolvam os conflitos de forma independente, melhorando suas habilidades de comunicação e gerenciamento de conflitos. Em última análise, para uma colaboração bem-sucedida, os membros da equipe precisam ser responsáveis e capazes de resolver seus próprios problemas.

Se forem obrigados a se envolver, os gerentes devem abordar isso de uma posição de mediação, e não de autoridade. Em outras palavras, eles devem ajudar as partes em disputa a resolver o conflito por conta própria, em vez de impor uma decisão autoritária. Claro, se a mediação não produzir resultados satisfatórios, alguma forma de decisão executiva será necessária.

Melhores práticas

Independentemente da natureza do conflito, seu contexto e o estilo preferido das partes envolvidas, há uma série de princípios e etapas universalmente aplicáveis que ajudam a gerenciar o conflito de forma saudável e construtiva. É uma espécie de código de conduta para lidar com o conflito desde o momento em que ele é reconhecido até sua resolução.

Estas são as melhores práticas para o processo de resolução de conflitos:

Reconheça a situação: entenda o que está acontecendo e comunique-se de forma clara e honesta.

Deixe que todos sejam ouvidos: permita que todos expressem suas opiniões e sentimentos. Antes que o processo de resolução de problemas possa começar, devemos primeiro reconhecer o que todos pensam e como se sentem. Certifique-se de que você está ouvindo verdadeira e ativamente as outras partes envolvidas.

Evite apontar o dedo: não antagonize ainda mais nenhuma das partes envolvidas acusando e colocando a culpa nelas. Em vez disso, expresse sua própria perspectiva ("Eu sinto que...", "Eu acredito que...") e lembre-se de que o objetivo é ajudar a outra parte a entender seu ponto de vista e tentar encontrar um ponto em comum.

Defina o problema: conflitos podem escalar rapidamente e a causa da discussão pode facilmente se perder no barulho. Certifique-se de que a causa da disputa seja identificada com precisão para que ela possa ser tratada adequadamente.

Identifique a necessidade: a gestão de conflitos não está lá para determinar quem ganha o argumento, mas para encontrar uma solução que funcione para todos. Essa solução será alcançada de forma mais rápida e eficaz se reconhecermos as necessidades subjacentes das partes em disputa e pensarmos em maneiras de acomodá-las.

Tente encontrar um ponto em comum: encontrar áreas de acordo — não importa quão pequenas — é crucial para uma resolução bem-sucedida. O mínimo que as partes envolvidas podem concordar é a definição de um problema, o procedimento subsequente e os medos e preocupações que têm em relação ao problema. Concordar com pequenas mudanças em nosso lado do argumento mostra uma disposição para chegar a um resultado mutuamente satisfatório.

Trabalhe em uma solução: gere várias propostas, determine ações mutuamente acordadas, certifique-se de que todos estejam de acordo.

Navegue pelos conflitos no local de trabalho com o Pumble

Os conflitos no local de trabalho são inevitáveis, mas apresentam oportunidades de crescimento e melhoria dentro das equipes. Identificar e resolver conflitos de forma rápida e construtiva é essencial para manter um ambiente de trabalho saudável e promover a coesão da equipe.

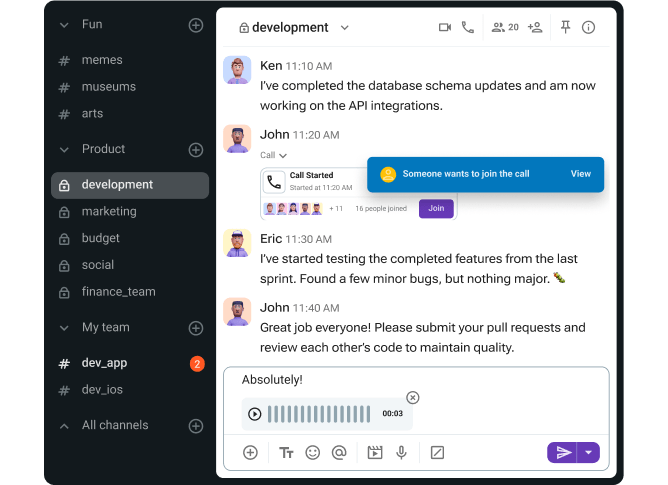

O Pumble, um aplicativo de comunicação de equipe projetado para colaboração, pode ser um recurso valioso neste processo.

Com ferramentas como mensagens em tempo real, conversas em threaded, e canais dedicados, o Pumble permite que as equipes se envolvam em diálogos abertos e abordem conflitos de forma proativa.

Além disso, a funcionalidade de pesquisa robusta do Pumble eas ferramentas de compartilhamento de arquivos facilitam a recuperação de informações e documentação relevantes, agilizando o processo de resolução de conflitos.

Ao fornecer uma plataforma para comunicação transparente e fácil acesso às informações, o Pumble capacita as equipes a navegar pelos conflitos de forma mais eficiente, resultando em equipes mais fortes e resilientes.

Capacite sua equipe a navegar pelos conflitos de forma mais eficiente — com o Pumble!

Como avaliamos esta publicação: Nossos escritores e editores monitoram as postagens e as atualizam quando novas informações ficam disponíveis, para mantê-las atualizadas e relevantes. Publicado: 17 de agosto de 2021

Publicado: 17 de agosto de 2021