If you’ve ever had to work on a project with other people, chances are, you have experienced Tuckman’s stages of group development firsthand.

The forming, storming, norming, and performing stages of group development indicate a path most teams need to take to reach a state of effective collaboration. Additionally, going through the initial 4 stages will help you arrive at the fifth stop on that road — the adjourning stage.

As you’ll soon learn, each of those phases comes with unique challenges and opportunities you can take advantage of.

But, taking advantage of a process would require you to understand the steps contained within it — which is what we’re here to help you with.

In this article, we’ll go through the:

- 5 stages of group development proposed by the American psychological researcher, Bruce Tuckman,

- Main markers of each phase as well as the transitions between these stages, and

- Examples of communication that illustrate each point in the process.

After discussing those points, we’ll also go over 2 critiques of Tuckman’s model.

So, without further ado, let’s start by establishing where this model even comes from.

Where do forming, storming, norming, and performing come from?

Forming, storming, norming, and performing are steps in the process of group development proposed by American psychologist Bruce Tuckman in 1965.

More specifically, these terms mark the milestones teams reach while they’re working on a project together.

More than anything else, the model is now used to envision how groups can reach their greatest potential and become efficient, collaborative teams.

In short, these terms — forming, storming, norming, and performing — signify the:

- Formation of a team in the beginning stages of a project,

- Interpersonal tensions that arise as people try to find their footing in the team and learn about each other‘s preferences,

- Normalization of relationships on the team as everyone comes to understand their roles and respect each others’ contributions, and the

- Unity that is reached as all the pieces fall into place and everyone starts performing their roles to the best of their ability.

There is also a fifth stage that was later added to this model, which marks the team’s dissolution at the end of a project.

Notably, this theory places a lot of emphasis on the team leader’s role as the person who can help the team transition between each of these stages rather than collapsing in on itself at the first sign of trouble.

But, these are only the rough strokes of this group development theory. To get past the surface level, we have to know how this model came about, in the first place.

🎓 Pumble Pro Tip

Before we delve into this subject matter, we should know what it takes to establish collaboration within a team. To learn more, check out this guide:

Tuckman’s stages of group development

In Bruce Tuckman’s words, the article he wrote for the Psychological Bulletin in 1965 never had any loftier goals than producing a theoretical model of the stages of group development that is representative of the research provided by existing literature at the time.

In addition to the forming, storming, norming, and performing stages of group development, the article also presented 2 other classifications found in research on small group dynamics. These classifications were based on the:

- Settings in which a group is found (group therapy, HR training, naturally-formed groups, and laboratory-task setting), and

- Realm into which the group behavior falls (interpersonal or task-driven).

Even so, Tuckman devoted most of his original paper to showcasing the 4 stages of group development he identified in research on different kinds of groups.

The now-famous terminology of forming, storming, norming, and performing came from the discussion segment of the paper. These terms were Tuckman’s shorthand for the events that take place during each of the stages he identified. The table below showcases the main components of the original phases of group development.

| Tuckman’s shorthand | Stage meaning | Task activities |

|---|---|---|

| FORMING | Testing and dependence | Orientation to task |

| STORMING | Intragroup conflict | Emotional response to task demands |

| NORMING | Development of group cohesion | Open exchange of relevant interpretations |

| PERFORMING | Functional role relatedness | Emergence of solutions |

More than a decade later, Tuckman wrote a follow-up article with collaborator Mary Ann Jensen, in which he examined 22 studies that came out between 1965 and 1977. As a result, they added a fifth stage to his model of group development — adjourning — which represents the termination of group activities.

With that being said, let’s talk about each of these stages in greater detail.

What are the 5 stages of group development?

Now that we know how Tuckman arrived at his 5 stages of group development, we can look at how groups move through these phases and what they all represent individually.

Going forward, we’ll discuss the:

- Individual stages of group development,

- Key points and processes that take place during each phase, and

- Transitional activities between stages.

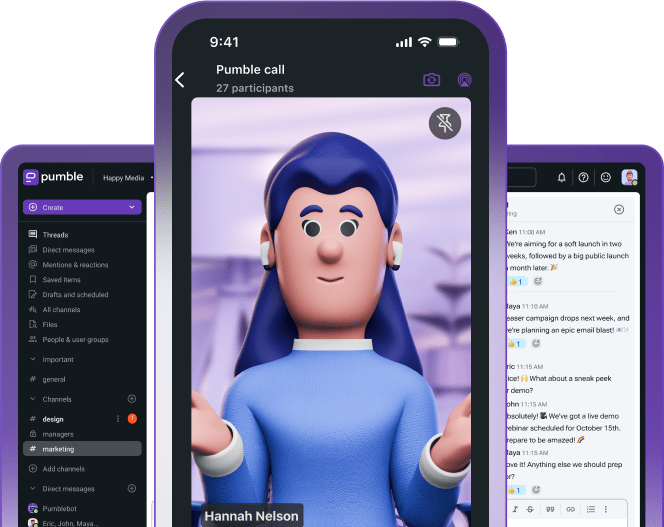

We’ll also show this progression through messages exchanged between members of a fictitious digital marketing team on Pumble — their internal communication software.

So, without further ado, let’s start with the forming stage of team development!

Step #1: Forming stage of group development explained

In Tuckman’s 1965 paper, the author initially marked the first stage he noticed in group development research as one of “testing and dependence.”

Of the 26 group development studies he analyzed, 18 identified the first stage with one (or both) of these terms. The term “testing” refers to the fact that group members typically use this phase to determine which interpersonal behaviors are acceptable based on the others’ reactions.

Another synthesis of group development studies Tuckman referenced identified hesitant participation as the first stage of group development. In line with that, during this stage, group members tend to fall back on politeness and formal communication as they take time to assess the other personalities on the team.

Aside from this reserve, the prevailing emotions that are felt are optimism and anticipation, with a dose of teamwork-related anxiety added for good measure.

In reference to the group’s main task, the forming stage corresponds with the identification of relevant parameters. Additionally, the team must determine how individual group members’ skills can be used to accomplish the group’s goal.

Overall, according to a 2021 comparative analysis of various group development models, Tuckman’s first stage is characterized by:

- A lack of role clarity, and

- A desire to assess the capacities and goals of fellow team members.

During this stage, a leader emerges to meet the team’s collective need for a unified vision. Additionally, most group members form an opinion about the others as well as the task they’ve been assigned.

Key points for the forming stage:

- The team comes together to complete a task/project.

- Relationships between members are polite and distant.

- Members attempt to gauge each others’ skills.

- They feel optimistic, curious, but also anxious.

- Boundaries are tested and ground rules are established.

Communication during the forming stage of team development

According to Christy Pruitt-Haynes, Global Head of Talent Management and Performance at the NeuroLeadership Institute, the forming stage is crucial to the success of the team and its project:

“That’s when you establish why everyone is on the team and what the team is working towards. During that phase, you have the biggest opportunity to mitigate against bias and set the team up for success. […] Without that clarity, it is almost impossible for the team to work as a unit, acknowledge and appreciate the different skills everyone brings to the team, and plan a strategy on how to accomplish its goals.”

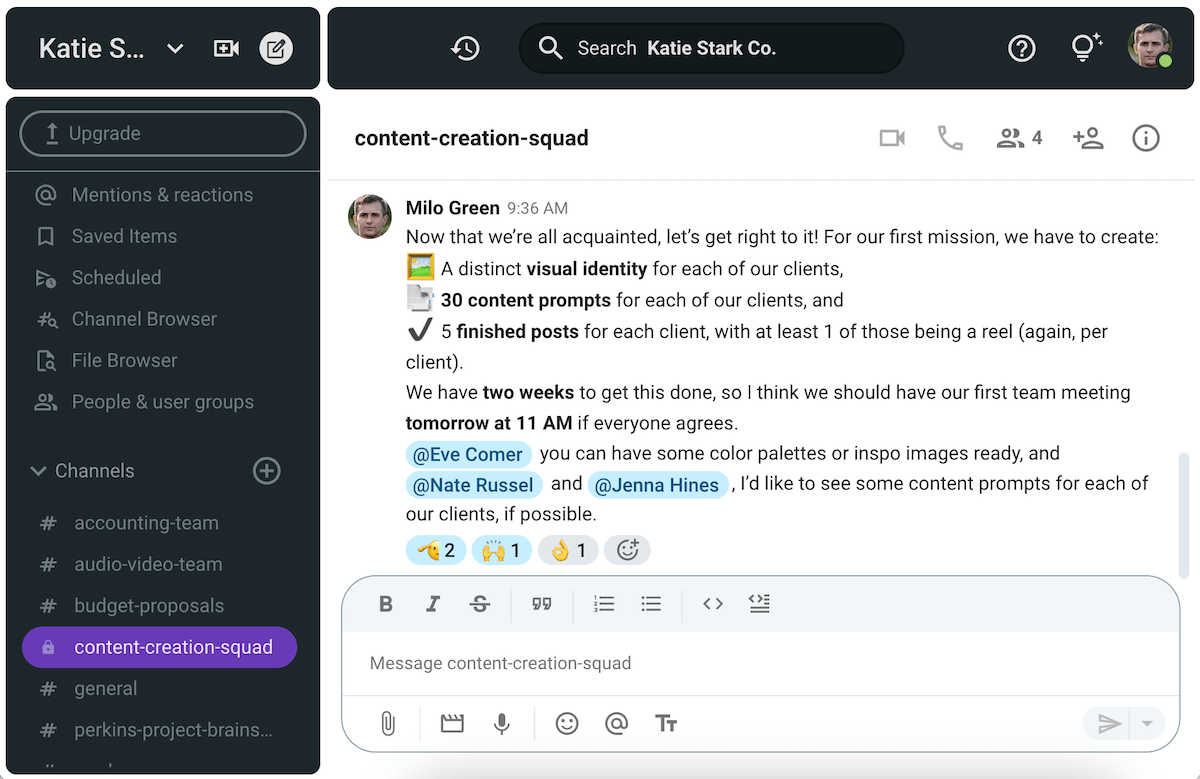

So, what would a productive forming stage look like for our fictitious digital marketing team?

Improve team communication with Pumble

At this point, individual team members may not fully understand the team’s purpose, how they’ll fit in, and whether they’ll collaborate well with others. So, the main objective of this first interaction is to break the ice and set everyone at ease.

After that, groups usually turn to their leader for direction. In response, the leader might leverage everyone’s excitement to introduce the first task the group needs to complete, as shown below.

Of course, not all teams get to set off on their project with such ease. Even so, most groups will need to hit certain milestones before moving to the next stage.

🎓 Pumble Pro Tip

Team leaders can use the forming stage to set their teams up for success. To learn more about that, read this article:

Moving from the Forming to the Storming stage

According to Christy Pruitt-Haynes, identifying the team’s goal and the member’s strengths should be the primary goal of the forming stage:

“When moving from forming to storming, it is important to ensure everyone is aligned on what the goals are and who everyone is (their role on the team, why they are there, and what their strengths are). […] As a team, this is when you are most likely to acknowledge the differences you all have in skills, mindset, and background.”

CEO of Culture at Work with decades of experience in leadership coaching, Carol Wilson, added that empathetic leadership plays a vital role in transitioning groups between stages:

“Time invested by the leader and the team members in listening to and empathizing with the others in the Forming stage will pay off substantially further down the line. Expectations and job descriptions should be clearly laid out and the leader should role model the behaviour they would like to see the team exhibit.”

Professor and Chair of Organizational Leadership at Utah Valley University and member of the Forbes Coaches Council, Jonathan H. Westover, noted that communication is the key to effective transitioning between stages:

“To help teams transition between the various stages of group development, I recommend:

- Open communication,

- Setting clear expectations, and

- Providing regular feedback.

The team leader should also be aware of the team’s progress and be willing to adjust their leadership style accordingly.”

In short, leaders must encourage the team members to develop a level of understanding and appreciation toward one another to smooth the transition between stages of group development.

🎓 Pumble Pro Tip

Knowing how to listen to the people you work with will deepen your understanding of them. Check out:

Step #2: Storming stage of group development explained

Going back to Tuckman’s 1965 paper, we can see that the second stage of group development was initially labeled as a phase of “intragroup conflict.”

In other words, this stage represents a time when the group members become hostile toward one another. They start challenging each other — as well as their leader’s authority.

In the aforementioned 2021 overview of various group development models, the second stage is characterized by:

- A struggle for leadership roles,

- Compromises and uncertainties, and

- A risk of dismantling due to emotions and relational issues.

Ultimately, these disputes are the result of members struggling against group assimilation. Communication becomes more difficult as different personalities come into play, leading to infighting.

According to Tuckman, this stage is also exemplified by emotional responses to task assignments. In other words, group members begin to have emotional reactions to work-related requests from other group members or leadership.

Key points for the storming stage:

- Individuals resist assimilation.

- They challenge each other and the leader’s management style.

- Team members exhibit emotional responses to task assignments.

- They feel anxious and defensive.

- The stage ends with a clear division of responsibilities.

Communication during the storming stage of team development

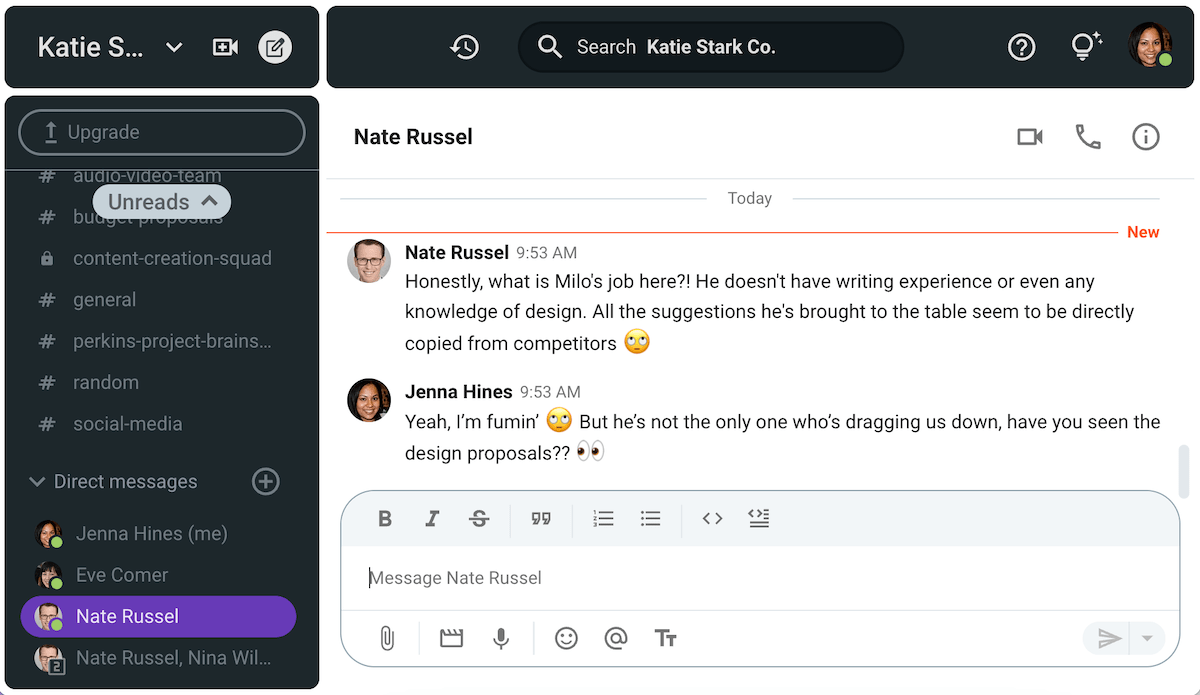

As we have established, the storming phase of group development is exemplified by conflict, friction, and resistance to assimilation. During the stage, most people tend to drop their polite facades and show their true character.

Of course, this pushback doesn’t always transform into outright verbal confrontations. Rather, members can form cliques within the group, which can damage the overall structure of the team.

Not discussing the underlying cause of these tensions can cause the group to linger in this stage for longer than necessary. So, a lack of conflict would be just as dysfunctional as prolonged disputes among team members.

According to Christy Pruitt-Haynes, effective leadership is necessary to keep teams on track:

“The speed at which a team moves from one stage to the next depends on several factors, and each team needs to work through them efficiently but completely. It is better to be thorough than rushed; but, at the same time, an effective leader looks for signs that the team is stuck and, when that occurs, they move them along.”

However, Jonathan H. Westover cautions against rushing through the stages of group development, saying that:

“Managers should not rush their teams through the beginning stages. Each stage is essential for the team to develop and perform effectively. Allowing a team to linger in a certain stage can be beneficial if it is necessary for the team’s growth.”

With that in mind, let’s take a moment to consider what it takes to transition the group from this stage to the next.

Moving from the Storming to the Norming stage

Christy Pruitt-Haynes also mentioned that the main question team leaders should ask themselves when transitioning their team toward the norming stage of group development is “How?” More specifically, she says the questions should be:

“How will we engage with each other, how will we work through conflict, how will we hold each other accountable, and how will we push back respectfully when we need to?

During the storming phase, a team is most likely to resent the differences in work styles, backgrounds, and skills. However, in order to move to norming, that needs to shift from resenting to accepting those differences. The goals for this transition include:

- Being able to work through conflicts while preserving relationships,

- Being aligned on what the priorities are and what the limitations are.”

Carol Wilson told us that conflict resolution should be the team leader’s main task during this stage, and even mentioned that, once again, it’s all about encouraging understanding:

“[Conflicts] can be resolved by helping members understand that, although other members may think and work in different ways, or hold different opinions, such diversity strengthens the team by providing a wider range of knowledge, skills, and resources.

Each member should try to deliver sincere positive feedback to the others, working towards stable relationships where suggestions will be viewed as contributions rather than criticisms.

The leader should let go of the small stuff and encourage people to approach tasks in their own way wherever possible.”

These ideas were succinctly summed up by Maria Szandrach, CEO of Mentalyc who also holds an MSc degree in Management from London Business School. She noted that leaders should:

“Encourage active listening, provide a platform for conflict resolution, and promote collaboration and compromise. Facilitate discussions to establish shared norms, values, and processes.”

Step #3: Norming stage of group development explained

The norming stage of team development is when the discontent and tension of the storming stage dissipate. As the term “norming” suggests, this is when participation in group activities becomes normalized. The task conflicts that marked the previous phase of group development are set aside in favor of ensuring harmony.

Since this phase allows group members to reach a consensus, many think of it as the crucial turning point in the process of group development. According to Jonathan H. Westover, this is when the group agrees to resolve internal disagreements:

“[The norming] stage is where the group establishes clear norms and expectations, which helps to avoid future conflicts. A well-established norming stage can lead to a high-performing team.”

The team is now able to operate as a cohesive unit, as members accept each other’s idiosyncrasies and their own position within the group. Leadership becomes more open and decentralized as members feel more comfortable with each other and offer more constructive feedback instead of criticism.

That might be why one of the studies Tuckman referenced in his original paper described this stage of group development as “one of freedom and friendliness supportive of insightful behavior and change.”

Key points for the norming stage:

- Team members accept their roles within the group.

- They come to terms with the other members’ idiosyncrasies.

- There is an emergence of insight, as everyone becomes more receptive to feedback.

- Group communication becomes more open as members share task status updates amongst themselves.

- The group encourages creativity and harmony.

Communication during the norming stage of team development

As we have established, the various processes that take place during the norming stage allow members to become much more transparent with each other. In other words, communication becomes more open and honest.

According to Christy-Pruitt Haynes, norming helps groups prepare to anticipate and mitigate problems as they arise, without blaming team members when things go astray:

“Teams understand that they are more productive because of the diverse skills represented… […] They know and trust their team members and are most likely to give them the benefit of the doubt if something goes wrong (as opposed to pointing fingers when problems arise in earlier stages). ”

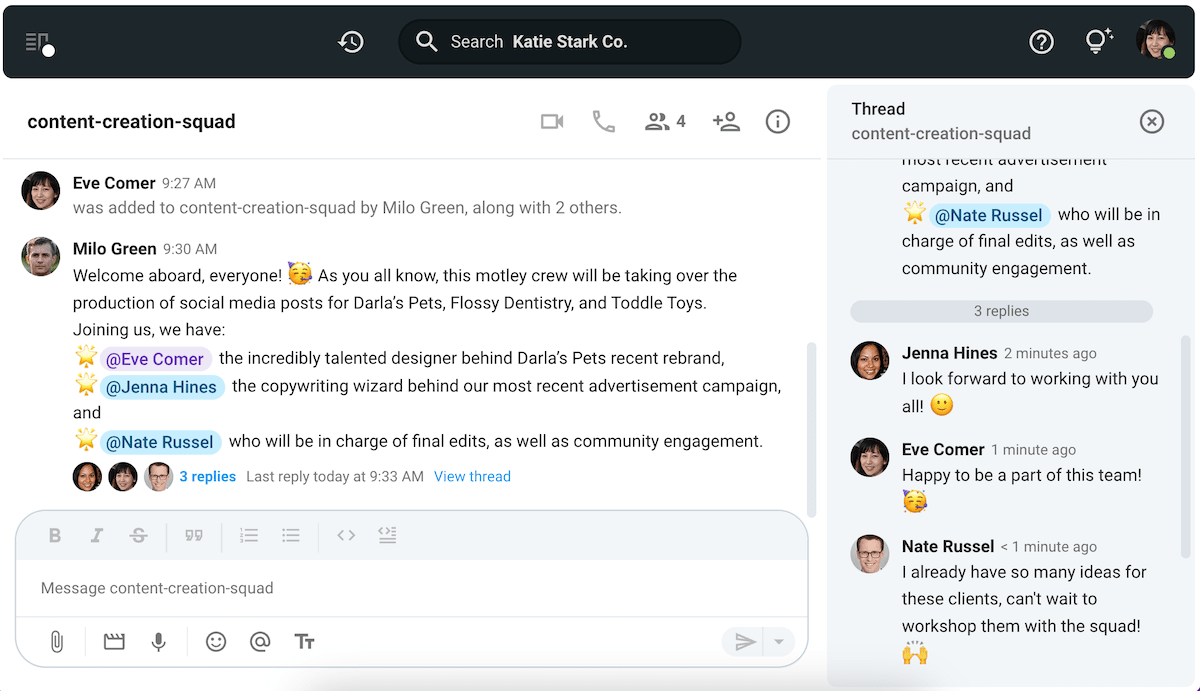

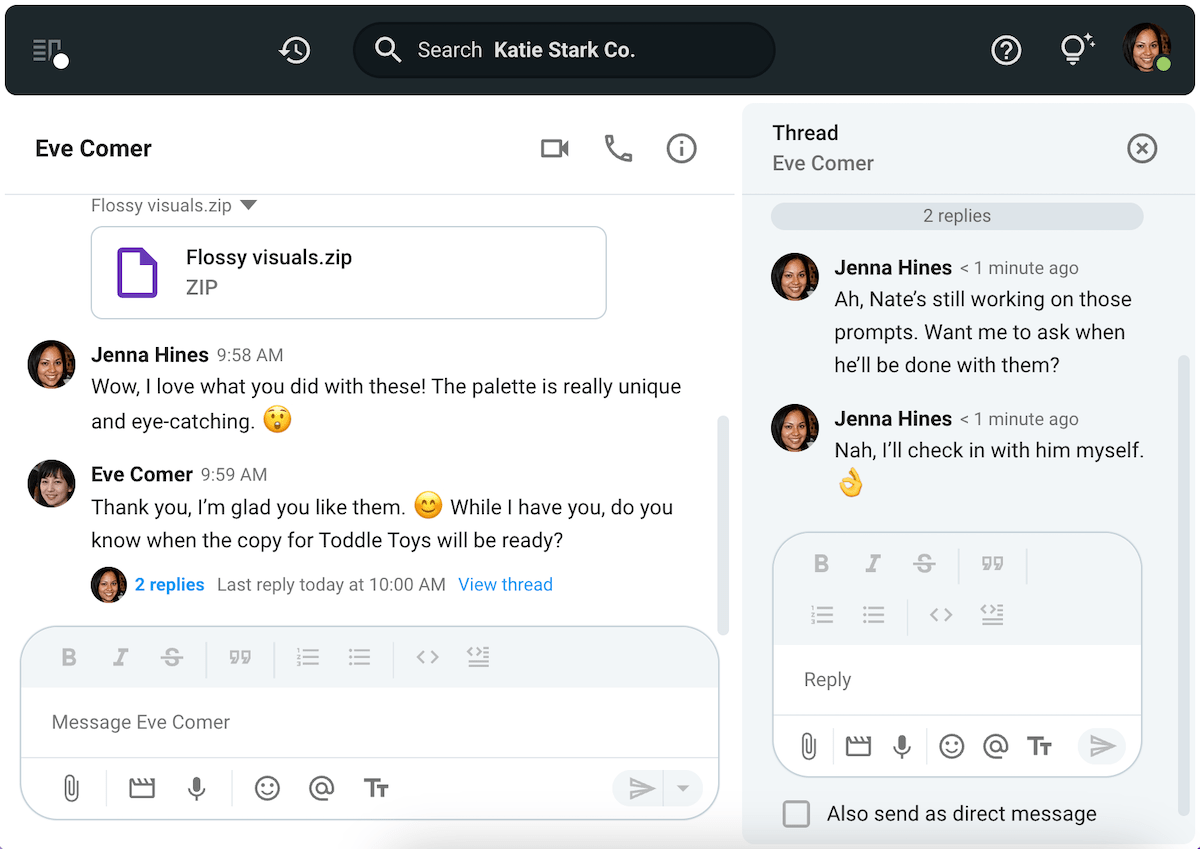

Another factor that affects group communication during this stage is the establishment of rules, roles, and processes. That means that members are no longer confused as to who they should contact about certain issues or who has which responsibility on the team. Here’s an example of what that kind of communication might look like.

Reach out to relevant people in Pumble

As we can see, Eve the Designer doesn’t feel like she has to reach out to Nate the Editor through a third party. Instead, she can direct her question to the person who’s working on the task she’s interested in.

This allows the team to start operating at a higher level, which will eventually let them enter the performing stage of group development. With that in mind, let’s see what the experts have to say about how groups move from norming to performing.

Moving from the Norming to the Performing stage

According to Carol Wilson, transitioning from the norming stage to the performing stage will require leaders to adjust their communication style:

“Leaders should use a coaching approach and ask the team for their solutions before giving the leader’s own. A team at the Norming stage will have much to offer in terms of experience and ideas which, if accessed, can save leaders time and energy, leaving them free to focus on the wider horizon, for example, broadening the scope through strategic partnerships and succession planning.”

Therefore, a key part of the transition between norming and performing is being able to rely on team members to perform project-related activities.

To that end, leaders will need to be able to recognize and utilize individual members’ strengths. According to Maria Szandrach, that’s how leaders can get their teams to move from norming to performing:

- “Foster a supportive environment,

- Recognize and leverage individual strengths,

- Encourage autonomy and ownership, and

- Provide resources and support to enable high performance.”

Having said that, let’s see what happens when teams finally hit their stride and reach peak performance.

🎓 Pumble Pro Tip

Before discussing the performing stage of group development, let’s take a moment to consider what makes a team productive. This guide should help:

Step #4: Performing stage of group development explained

In Tuckman’s analysis of group development models, the stage when the relationships within a group normalize is usually followed by one when the team finally becomes functional. In other words, it becomes an entity capable of problem-solving, as each member settles into their role and understands the roles of others.

Maria Szandrach notes that reaching this phase is something most team leaders strive toward, saying:

“While all stages of Tuckman’s model are crucial, the performing stage is often considered the most important. At this stage, the group has:

- Successfully navigated the initial challenges,

- Established clear norms, and

- Is functioning at a high level of productivity and collaboration.

The performing stage represents the achievement of the group’s potential and the ability to deliver optimal results.”

One of the studies he included in his synthesis labeled this final stage as one of “positive independence” which is “characterized by simultaneous autonomy and mutuality.” So, the members of a team in this stage of group development can execute the tasks assigned to them independently while also acting in the greater interest of the group.

Tuckman himself labeled this stage as one of “functional role-relatedness” — indicating that group members are ready to fully embody their roles and enhance the group’s task activities.

Ideally, this phase would last until the project the group was formed around was completed. Then again, different circumstances may change the direction of the group development — as we’ll discuss when we get to the critiques of this model.

Key points for the performing stage:

- The group enters peak performance mode.

- Members act independently while also working as a team.

- The group acts as a sounding board and support system.

- Communication is harmonious and open.

- Meetings are shorter and less frequent due to a lack of miscommunication.

Communication during the performing stage of team development

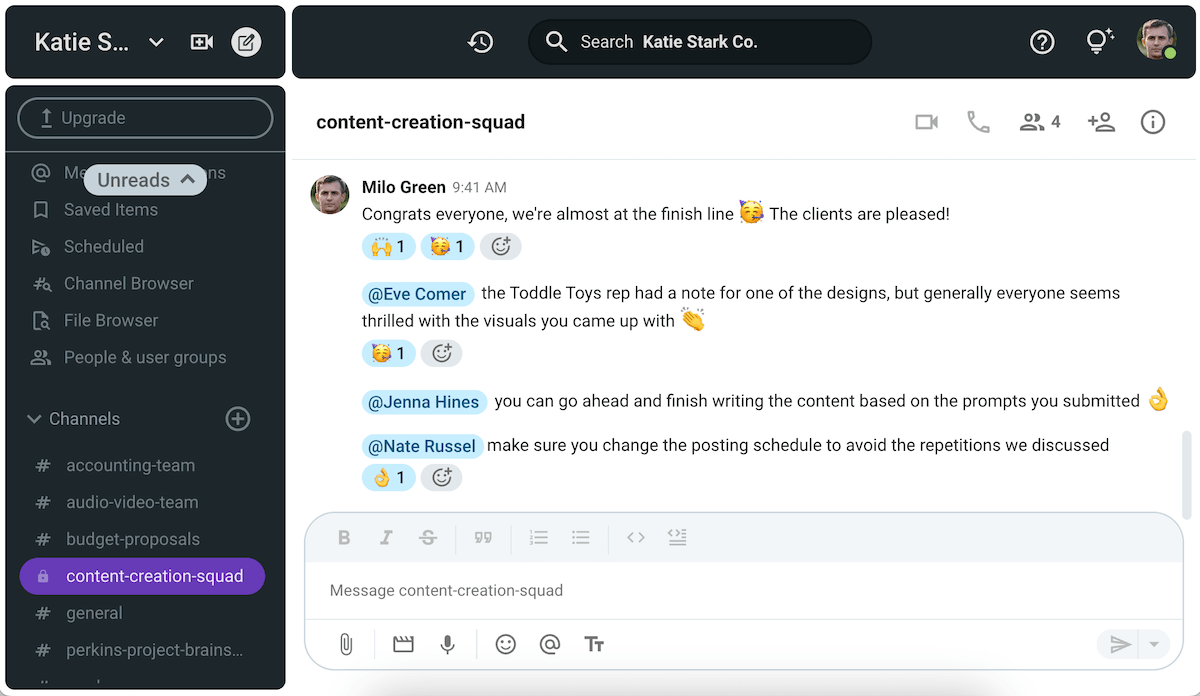

According to the 2021 overview of group development theories by Vaida and Şerban, the performing stage represents peak efficiency and coordination within the team. Most processes occur smoothly and interpersonal relationships flourish.

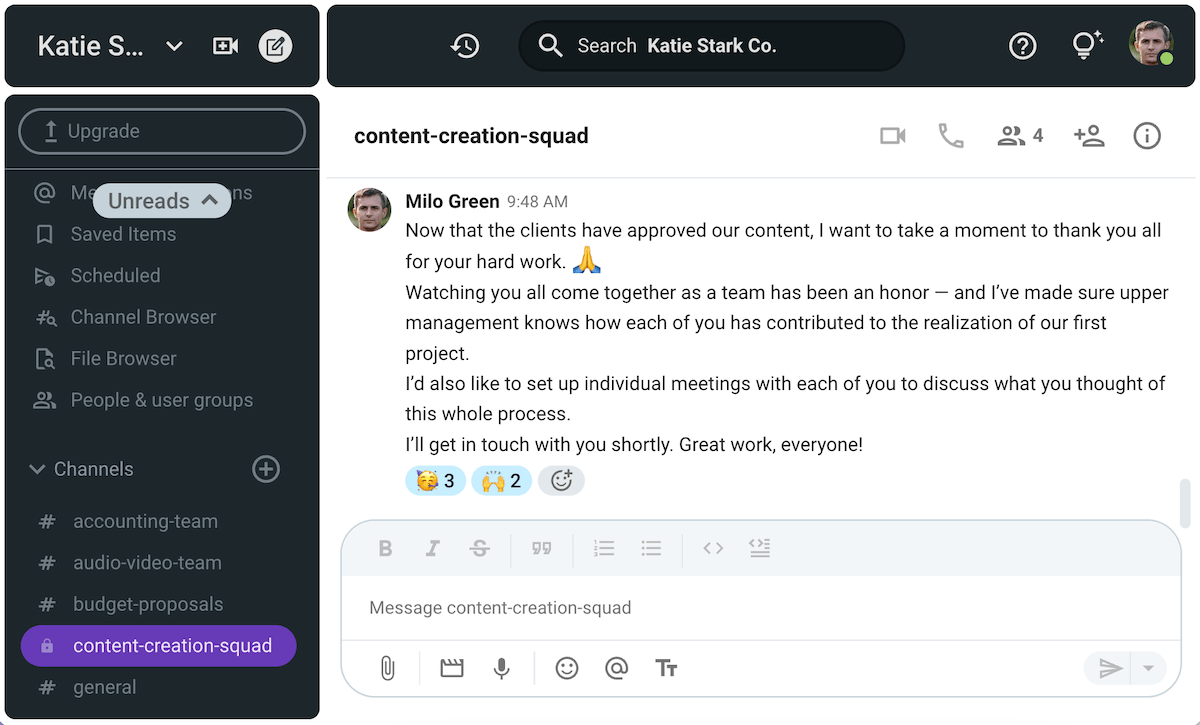

So, for this stage, communication should be pretty uneventful, with members sharing status reports and having friendly exchanges with each other. As the adjourning stage approaches, members may become more interested in celebrating each other’s successes, as seen in the image below.

Celebrate your team with emojis in Pumble

Moving from the Performing to the Adjourning stage

At this point, we’ve reviewed all of the original 4 stages of team development Tuckman identified in his 1965 paper. But, how does a group move from the original final stage, performing, to the adjourning stage?

Most of the experts we have spoken to have agreed that the performing stage is the ideal time for laying the groundwork for an upcoming group disbandment.

According to Christy Pruitt-Haynes, it comes down to being able to acknowledge individual and group successes:

“Each member should be able to articulate what they did, what they learned, and what they taught others. One mark of a successful team or project is how each person grew during the process.

If the team did a good job outlining the goals and measures of success, adjoining should be a fairly easy process because everyone sees the end of the project coming and ideally feels good about their contribution.”

Carol Wilson also noted that the team leader should also get some recognition during this time:

“The leader and team members should show recognition for the contributions of others and ensure that credit is awarded where due. This applies as much to team members validating the leader as the other way around.

If anyone is left feeling that their contribution is not being recognised, the resentment may regress the team back into the Storming stage, or be carried through to the next project and Storming will be proportionately harder to overcome in the future.”

Sharing these acknowledgments will create optimal conditions for a satisfying termination of the group.

Step #5: Adjourning stage of group development explained

After examining research on the life cycle of small groups, Bruce Tuckman and Mary Ann Jensen recognized that Tuckman’s original model neglected to propose a phase in which the group members disengage from one another and terminate group activities.

To make up for it, they introduced the adjourning stage, which represents the “death of the group.”

Carol Wilson summed it up perfectly:

“Adjourning, a stage that Professor Tuckman added in 1977, is a time for:

- Thanking people,

- Recognition of individual achievements,

- Reflection on how far the team has come, the turning points along the way, and what its members can take forward from the team to the future.”

In addition to celebrating group achievements, Wilson stressed the importance of notifying external stakeholders about collective and individual achievements during this stage in order to set the stage for future successful collaborations.

However, Christy Pruitt-Haynes noted that this stage isn’t always celebratory. As group activities come to a stop, anxiety may creep in:

“Team members may not know what is next for them but in most cases, one successful team experience makes anticipating the next a little easier. As a final step, teams should have a post-mortem to discuss what they did well, what they would change, and how to move forward.”

Ultimately, the adjourning stage of group development is crucial because it encompasses all the processes that anticipate the disbandment of the group. As such, it’s only natural that some group members may experience separation anxiety, right alongside feelings of accomplishment.

Key points for the adjourning stage:

- The project around which the group was formed is complete.

- The members discuss what went wrong and what went right.

- They share feedback amongst themselves.

- The team leader informs external stakeholders of the group’s accomplishments.

- The group celebrates the successful completion of a project.

Communication during the adjourning stage of team development

Having completed the project the group was formed around, members look back at the process of psychological development they went through.

Each person can see how they have changed since the beginning of the project individually and as a team player. They can also note how their team members have changed, and share their findings.

Most notably, this is a stage when the role of the team leader once again becomes crucial. Namely, the leader must now dole out feedback or, rather, feedforward to help group members solidify the knowledge they have gained while working on the project.

Moreover, as we have previously mentioned, they must share those insights with external stakeholders. In the case of a professional environment, those can be either higher-ups within the company or external partners and clients. This will make team members feel appreciated, as shown in the exchange below.

In this particular case, we can assume that creating one month’s worth of social media content for several clients is the end of one chapter in this group’s life cycle. However, if they continue working on the same type of task month after month, they may continue to cycle through the stages we have discussed.

Does that fit with Tuckman’s original vision of team development? To get to the bottom of that question, let’s talk about the critiques of Tuckman’s stages of group development.

Critiques of Tuckman’s model of group development

In Tuckman’s 1977 follow-up article, Mary Ann Jensen reminded us that Tuckman’s original paper noted the limitations of the literature he used to extract his hypothetical model. Namely, Tuckman mentioned that there was an overrepresentation of therapy and training group settings in the literature. Thus, making generalizations that also applied to the development of groups in natural and laboratory settings proved difficult.

Even so, not many of the experts we have spoken to noted this omission when talking about the limitations of Tuckman’s stages of group development. Rather, the critiques they were familiar with usually came down to the model’s:

- Reliance on linear progression, and

- Emphasis on group behavior over individual and external factors.

However, many experts today have found workarounds for these omissions.

Point #1: Tuckman’s model could be read as being overly reliant on linear progression

Jonathan H. Westover told us that one of the biggest criticisms of Tuckman’s model is that it assumes a constant linear progression:

“One of the main criticisms of Tuckman’s model is that it assumes a linear progression through the stages. In reality, groups can move back and forth between the stages, and some groups may never reach the performing stage.”

Maria Szandrach explained why this may present a problem:

“Group development is often more fluid and non-linear, with stages overlapping or revisited.”

In other words, teams often move back and forth between stages, even during a single project. Researchers have long been aware of this omission, as evidenced by Jack K. Ito and Céleste M. Brotheridge’s paper Do teams grow up one stage at a time? Exploring the complexity of group development models.

Upon surveying 204 public servants in Canada, this study concluded that, while most teams followed the predictable group life cycle, many didn’t. According to the researchers, the difference lies in how successfully a group navigates challenges. That’s why particularly contentious stages of group development — such as the storming stage — may occur several times.

Furthermore, individuals can go through these stages at different times, as Christy Pruitt-Haynes noted:

“When an employee first joins an organization they immediately start at the forming stage. So, Tuckman’s process doesn’t just apply to newly formed teams, it applies to each individual joining an established team. It serves as a reminder that teams are in a constant state of flux and that that flux applies to each of us.”

But, while we’re on the subject of individuals, let’s talk about the other point of contention we have mentioned.

Point #2: Tuckman’s model doesn’t sufficiently recognize the influence of individual and external factors

The second critique we heard from the experts we spoke to was that Tuckman’s model places too much emphasis on group behavior over individual factors and external factors. Maria Szandrach mentioned some of the factors the model doesn’t account for, saying:

“Some argue that Tuckman’s model does not sufficiently account for factors such as individual personalities, diversity, or external influences on group dynamics.”

However, it’s difficult to call this an outright omission of Tuckman’s model. After all, the storming stage he included could be seen as the direct result of individuals working through their differences.

In any case, as with the previous critique, people usually find ways to adapt Tuckman’s model in a way that accounts for these differences.

Still, being aware of these critiques allows us to be more intentional in our attempts to apply the model to real-life teams. More than anything, it allows us to conceptualize Tuckman’s stages of group development as a theoretical model that accommodates fluidity.

As Carol Wilson told us, Tuckman’s stages of group development are a “simple, robust, and enduring model,” adding that:

“It does not provide solutions but does not set out to do that.”

In saying this, Wilson reminds us that Tuckman’s original works on this matter, published in 1965 and 1977, never offered any tips for navigating the forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning stages.

Instead, they merely described what different teams go through during each of those stages. Everything else was added to the theory at a later date and is thus subject to interpretation.

Leverage Tuckman’s model with Pumble for effective team development

Ultimately, Tuckman’s stages of forming, storming, norming, performing, and adjourning showcase the collective psychological development a team goes through while working on a project.

However, successfully navigating these stages requires more than just theoretical understanding — it demands practical tools and effective communication strategies, and that is where Pumble comes in.

An all-in-one team communication app, integrating Pumble into your workflow and leveraging its features can help your team navigate Tuckman’s model more effectively. With Pumble, teams can ensure that all members are progressing through the stages together and address any differences or challenges that may arise along the way.

Furthermore, Pumble’s ability to adapt to the unique needs of different teams makes it an invaluable tool for applying Tuckman’s model in various contexts. Whether teams are newly formed or already established, Pumble empowers them to work cohesively towards a shared goal and achieve peak performance.

Incorporate Pumble into your team’s workflow and unlock its full potential

How we reviewed this post: Our writers & editors monitor the posts and update them when new information becomes available, to keep them fresh and relevant. Published: June 28, 2023

Published: June 28, 2023