Having effective and empathetic listening skills is crucial for establishing good workplace communication.

In addition to helping us work through any issues that might come up faster, active listening also allows us to avoid workplace conflicts and misunderstandings altogether.

But ultimately, everyone can benefit from being a good listener — and not just in the office.

In this article, we’ll talk about:

- The academic roots of active listening,

- The benefits of implementing the practice in your everyday life as well as your professional career, and

- Some practical tips for making that happen.

So, without further ado — let’s get started!

What is active listening?

The concept of active listening has a long and storied history in both the popular imagination and scientific discourse.

With that being the case, we aren’t able to present a single active listening definition most people stick to.

However, having researched the matter extensively, we could start by saying that active listening is, in essence, a set of techniques we might use to show that we are giving our undivided attention to our conversational partners.

Essentially, it is an attempt to understand the entire message someone is communicating, textually and subtextually, through spoken or written words, nonverbal cues, and context clues.

In addition to making an effort to listen, understand, and retain the information we are presented with, active listening is also about finding and executing appropriate or encouraging responses.

Of course, the practical aspect of this method has shifted quite drastically since its introduction.

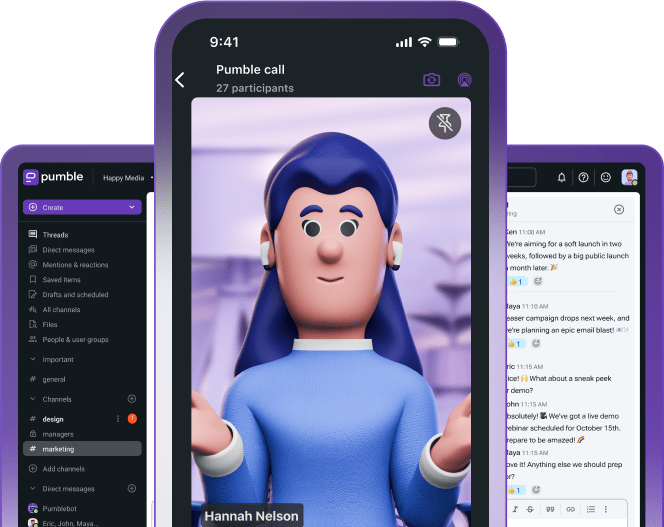

To illustrate that point, let’s see what an example of active listening from Carl Rogers’ and Richard Farson’s 1957 paper might look like in a modern context.

Would you believe the above words served as an example of a successful implementation of active listening in a professional setting?

Nowadays, we’d likely see the supervisor’s words as being sarcastic — and therefore not very helpful in the face of the foreman’s honest complaint.

Luckily, this article should show a more modern approach to active listening.

But first, let’s see how the term fits in, or rather encompasses, a related concept we came across while researching this topic — passive listening.

Passive vs Active listening

The concept of active listening supposes that, to be a good listener, you would need to do more than simply sit there and absorb the information you are being presented with.

Sticking to that would make you more of a passive listener — someone who doesn’t provide any sort of feedback in response to the speaker’s message.

Conversely, according to Ronald Adler’s textbook on interpersonal communication, mindful (or active) listening consists of five separate but simultaneous processes:

- Hearing, which is the physiological aspect of listening, accomplished by simply not being able to ignore audio input,

- Attending, or rather filtering through the information you’re picking up and zeroing in on what really matters, based on what you’re looking to gain from the conversation,

- Understanding, which requires us to read between the lines and discover the speaker’s true intent and real meaning,

- Remembering or memorizing the contents of the message through repetition, and

- Responding by giving observable verbal and nonverbal feedback to the speaker, thereby encouraging them to keep talking (or, in modern times, perhaps texting).

Yet, in order to become an expert at active listening, one must first create the right conditions for it. So, let’s see what those might be.

Conditions of the active listening process

Most researchers would agree that the term ‘active listening’ came about in the early 1950s, when it became a cornerstone of humanistic psychology.

Throughout the 1940s, psychologist Carl Rogers worked on developing so-called person-centered therapeutic methods.

During the course of his research, he wanted to highlight what he felt were the most crucial conditions therapists need to achieve in order to have effective sessions with their clients.

Now, even though most of us aren’t looking to become psychotherapists, we can all agree that therapists can serve as an excellent example of what mindful listening looks like.

With that in mind, let’s go through Rogers’ conditions of the therapeutic process as summarized in his paper, A theory of therapy, personality, and interpersonal relationships, as developed in the client-centered framework.

To begin with, Rogers believed that effective counseling would require:

- Two people, the client and the therapist, to establish contact.

- The client to be in a state of incongruence, vulnerability, or anxiety.

- The therapist to be congruent in relation to the client, meaning that they have an understanding of the client.

However, the latter three of Rogers’ six conditions will be more relevant to our study of active listening. These three require the therapist — or, in our case, the listener — to have:

- Unconditional positive regard toward the client (or, rather, the speaker),

- An accurate empathetic understanding of the client’s internal frame of reference, and

- The ability to show the client proof that the previous two conditions were satisfied.

In other words, these conditions are about the listener’s open and positive attitude and their ability to convey it to the speaker through verbal and nonverbal responses.

What are the 3 A’s of active listening?

Over time, the concept of active listening, as well as the theoretical tools we use to deconstruct and understand the practice, have evolved.

Instead of thinking about effective listening through the prism of Rogers’ therapist/client framework, people tend to talk about the 3 A’s of active listening:

- Attitude,

- Attention, and

- Adjustment.

After all, who doesn’t love alliteration?

At this point, you may have some inkling as to how these terms fit into what we already know about the active listening process.

Still, taking a moment to examine them individually might help us gain a greater understanding of the practice.

A #1: Attitude

Going back to Carl Rogers and his contemporaries, we saw an emphasis on the listener’s attitude toward the speaker.

Having an unconditional positive regard for whoever is speaking is one way of making ourselves more receptive to what they have to say.

Being open-minded in this manner should prevent us from automatically judging the value of what we’re hearing.

Additionally, Rogers’ requirement of an empathetic understanding forces us to place ourselves into the speaker’s shoes.

In effect, that means that we are absorbing new information through the prism of everything we know about the speaker already.

To offer an overly simplistic example, when talking to a coworker who had just come back from sick leave, we would naturally take that into account if they misspoke or exhibited certain nonverbal cues that don’t fit into the context of the conversation.

Having this kind of receptive attitude would also prevent us from being overly reactive or interrupting the speaker.

Ultimately, we must at least appear as though nothing the speaker is saying is beyond our understanding.

A #2: Attention

As you can imagine, paying attention to what someone is saying is a crucial part of the active listening process.

However, we shouldn’t only focus on the verbal (or textual) part of their communication.

We’ve already mentioned nonverbal cues, so this won’t come as a surprise. Namely, being able to accurately interpret someone’s body language is the key to our overall comprehension of their message.

Even if you can’t see someone, if you’re not in an in-person meeting or on a video call, you’ll find a wealth of information beyond the textual part of their message.

For example, if you’re on a voice call, you can listen to the tone of their voice and try to determine what’s not being said.

If you’re exchanging direct messages, you can still figure out if their texting pattern has changed, and if so — try to understand why.

Basically, your attention should be fully focused on the speaker. In addition to being able to detect these subtle clues, concentrating on the person you’re talking to will make them perceive you as a good listener.

A #3: Adjustment

Finally, the third A of active listening stands for ‘adjustment,’ meaning that the listener needs to be able to adjust their response to the speaker.

Basically, the listener needs to be flexible enough to follow what the speaker is saying without making assumptions as to what their overall point is.

That is something we’ll discern by understanding the wider context and taking note of the speaker’s nonverbal cues.

The listener’s flexibility also comes into play through the feedback they offer.

According to some studies, those who are considered good listeners tend to:

- Ask and answer questions (to clarify meanings, learn more about the speaker’s perspective, or encourage elaboration),

- Provide reflective and relevant feedback (which includes paraphrasing the speaker to make sure we’re on the same page),

- Offer their own perspective by sharing similar experiences, and

- Respond nonverbally by making eye contact, nodding, and facing the speaker.

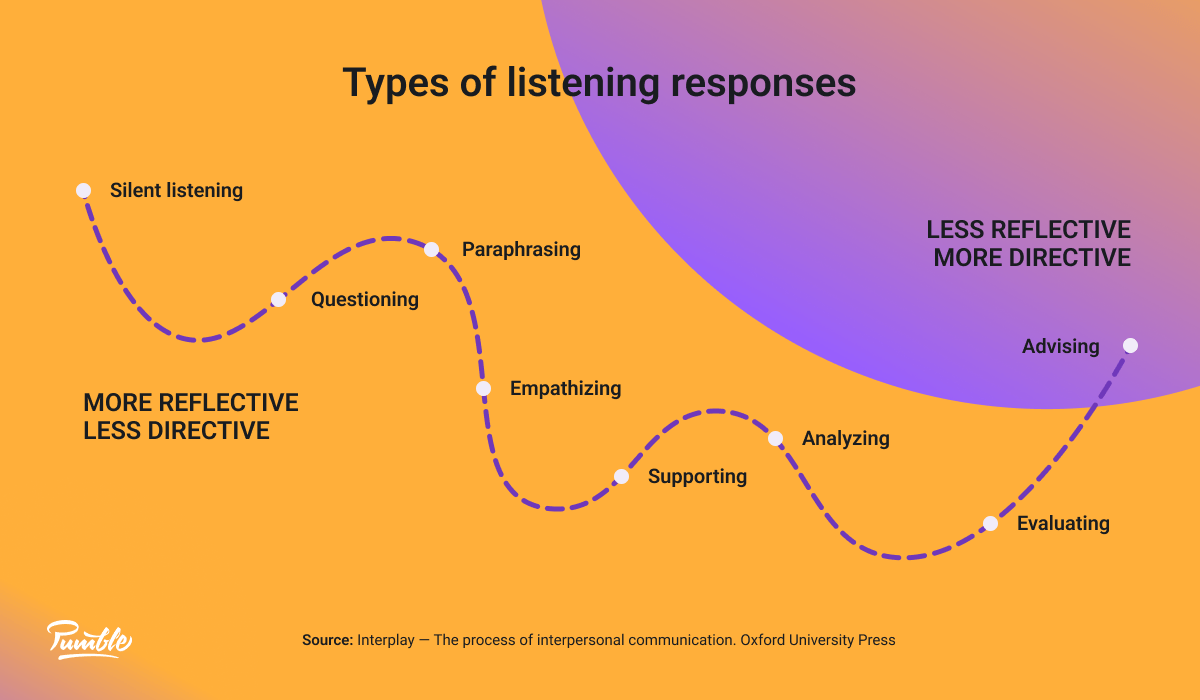

As we can see in the image below, Ronald Adler places a number of potential listening responses on a scale going from reflective to directive.

On the one hand, more reflective responses are a great way to show the speaker that we are paying attention to their story or presentation.

Conversely, more directive responses are better suited for situations that require us to share our own opinions or advice.

As we become better at active listening, we should be able to gauge which of these responses is the most appropriate for any given situation and adjust accordingly.

Ultimately, developing the skills you need to become an effective listener is sure to make you a better coworker, manager, employee, or boss!

Do you really need active listening at work?

At this point, you may be asking yourself how any of this can help you sharpen your professional communication skills.

And to be fair, a majority of business communication resources tend to focus almost exclusively on how you might transmit information more effectively, rather than how you can take it in.

Yet, as you can imagine, communication isn’t solely about stringing the right words together to get what you want.

As communication expert, Susan Peterson, would put it:

“Too many times, whether it’s with email, voice mail, or [the] Internet, we are concentrating on the art of telling, not listening. Yet good listening, in my opinion, is 80 to 90 percent of being a good manager and an effective leader. […] In your day-to-day meetings with customers, clients, or employees, if you listen — really listen with full eye contact and attention — you can own the keys to the communication kingdom.”

🎓 Pumble Pro Tip

If you don’t want to see your coworkers’ ideas fall on deaf ears, you should work promoting deep listening in your workplace. Here’s an article that might help:

The 4 faulty assumptions about listening

The quote we have just used comes from Communicating at work, a business communication textbook by Ronald B. Adler, Jeanne Elmhorst, and Kristen Lucas.

In it, the authors call attention to the four misconceptions people tend to have about the act of listening, particularly in a professional setting.

Namely, people often assume that:

- Effective communication is the sender’s responsibility. In other words, the one who is imparting a message is solely responsible for the way it will be received. However, as with any other type of communication, it is ultimately a two-way street. Just as the sender must put in the effort to clarify their stance, so too must the receiver try their best to understand the message.

- Listening is a passive exercise. Yet, as we have already established, effective listening should entail more than simply sitting in silence and letting the speaker say their piece. Rather, even if we’re not speaking, we need to be active participants in the conversation.

- Talking has more advantages than listening in a professional setting. If you subscribe to the “business bro” school of professional communication, you might believe that being able to “sell” someone on your ideas is the height of success. However, this article will attempt to show that being a good listener can influence people even more than sharing a convincing argument.

- Listening is a natural ability, rather than a skill you can hone. But, as you’ll soon find out, effective listening is about strengthening certain communication skills and removing the barriers that may affect our ability to absorb information.

With all that in mind, let’s take a look at the various skills we’ll need to become better listeners — and the hurdles we’ll have to overcome along the way.

What are the 8 active listening skills?

If you were to go online and look up the skills you’d need to develop in order to become a better listener, you’d probably get redirected to a list of active listening behaviors instead. The results of your query might tell you to:

- Discern the speaker’s underlying intent,

- Note the nonverbal cues the speaker is exhibiting,

- Refrain from judging the content or style of the speech,

- Keep your own body language open,

- Encourage the speaker through verbal cues,

- Ask clarifying questions if necessary,

- Reflect or paraphrase certain points to make sure you’re understanding correctly, and

- Share your insights when appropriate.

But, while these points do make a good active listening checklist of sorts, they don’t really represent any particular skill.

In other words, the list above doesn’t really point to any skills that might help you improve as a listener.

After all, how exactly would you be able to follow a tip that calls for you to ‘discern a speaker’s underlying intent’? Alternatively, how would you know what would be an appropriate time to share your insights?

With that in mind, we’ve decided to present a different list of active listening skills based on what we believe would help you become a more effective listener. Namely, you should strive to become better at:

- Nonverbal communication

- Paralinguistics

- Self-awareness

- Social awareness

- Empathy

- Emotional intelligence

- Critical thinking

- Memory retention

But, since just listing the skills you’ll need won’t get you anywhere, let’s see how you might develop each of them individually.

Skill #1: Nonverbal communication

When someone is sharing their thoughts with you, it’s customary to keep your eyes on them.

But, even though making eye contact is usually the best way to show that you’re paying attention, we can do that while also taking note of their:

- Posture,

- Proximity to the other people in the group,

- Command of the environment,

- Physiological signs of comfort or, rather, discomfort, and

- General body language.

These clues will allow you to understand the speaker’s position more clearly, which will, in turn, allow you to discern the deeper meaning of their message.

How do you learn more about nonverbal communication?

If you want to dive into the world of nonverbal communication, you should first familiarize yourself with the types of cues you might come across.

To learn more, you should look into:

- Kinesics, the interpretation of nonverbal behaviors like facial expressions, posture, hand movement, etc., and

- Proxemics, the study of physical distance between people and their body language in relation to each other.

Researching these two fields should help you understand what you should look for when trying to interpret someone’s body language.

After all, the way someone moves their body through space and in relation to other people will tell you a lot about the way they are feeling.

Learning that body language can reveal someone’s inner thoughts should also remind you that someone else could be picking up on the cues you’re sending out.

Still, if sending encouraging nonverbal cues doesn’t come naturally to you, learning more about them and incorporating them manually could help you become a better listener too.

Skill #2: Paralinguistics

The study of paralinguistics is another subcategory of nonverbal communication, even though it relies on the interpretation of the quality of someone’s speech.

Listening to the rhythm of someone’s speech, where they pause to emphasize certain words or even take a breath, can tell you more about their state of mind.

You should also pay attention to the speaker’s volume, pitch, and intonation, as well as any other vocal changes you might spot during the course of the conversation.

How do you listen for paralinguistic changes when someone is speaking?

If you want to improve your ability to detect paralinguistic changes in someone’s speech, you’ll first have to know their baseline.

So, in this case, having prior knowledge of the speaker’s vocal patterns is key.

If you’re attempting to analyze the paralinguistic qualities of a presenter you’re seeing for the first time, you may fall short no matter how much theoretical knowledge you have.

For example, you might detect a slight wavering of someone’s voice that may otherwise indicate that the speaker is seconds away from crying.

However, that wavering may just be the natural property of their voice — so keep that in mind if you’re looking to improve and apply this skill in your everyday life.

Communicate more effectively with your team in Pumble

Skill #3: Self-awareness

A dose of self-awareness is always a useful addition to any kind of interaction.

After all, when we know our own feelings, needs, and values, we can be more honest with both ourselves and our interlocutors.

That clarity allows us to build stronger relationships and be more confident when making decisions.

Yet, to reap those rewards, we have to possess both internal and external self-knowledge.

On the one hand, internal self-awareness allows us to identify our values and goals, as well as the reactions we want to inspire from others.

On the other hand, we also need to have an understanding of the way others actually see us, which is where external self-awareness comes in.

Keeping these factors in mind should remind you to control the way you appear to others.

In other words, being a self-aware listener will allow you to consciously adjust the way you’re responding to the speaker by controlling unsolicited verbal outbursts and distracting nonverbal signals.

How do you become more self-aware?

Ultimately, the key to becoming more self-aware is introspection. However, that’s not exactly something we could teach.

To gain a greater understanding of one’s inner values, some people recommend therapy, while others opt for more informal options such as meditation or journaling.

Either way, you’ll have to spend some time contemplating life’s greatest questions, including:

“What do I want my life to look like?”

“What do I really enjoy doing?”

“How do I want others to perceive me?”

Aside from that, you can also try taking psychometric tests or asking the people around you for feedback.

Ultimately, being aware of the discrepancy between the way others perceive us and the way we see ourselves should become our impetus to create a third reality that’s somewhere between those two.

Skill #4: Social awareness

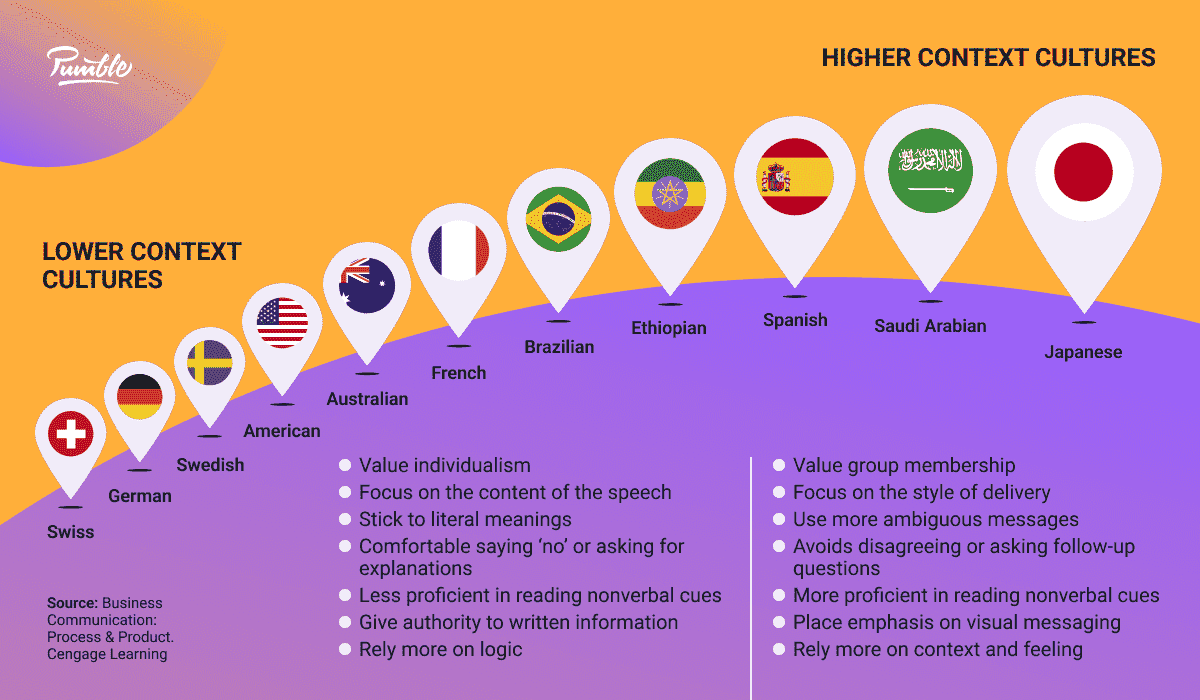

Egocentrism can drastically diminish our ability to understand what other people are trying to say, especially when their perspectives and lived experiences are different from our own.

Understanding the many social differences that exist between people can help us become better conversationalists in more ways than one.

After all, the way people speak and listen is invariably affected by their:

- Social class,

- Education,

- Race and ethnicity,

- Religious beliefs,

- Cultural background,

- Gender and sexuality,

- Age (or, more broadly, generation), and

- Disabilities.

These factors can affect everything from our behavior and the way we dress to the level of formality we are comfortable with and even our tolerance for conflict.

By refusing to engage with people on this level, we are essentially saying that we’re fine with always missing out on certain aspects of our conversations.

How can you broaden your social awareness?

The only way to expand one’s social awareness is to make a concerted effort to become culturally literate.

We can do so through formal education, such as workshops and books, or opt for more casual teaching materials like shows or movies depicting experiences that are different from our own.

Of course, we would need to be certain that those depictions are, in fact, credible.

In any case, we must avoid ethnocentrism at all costs and understand that diversity is a gift — in the workplace, and beyond.

Furthermore, we need to be able to adjust our behavior and avoid othering the already marginalized people around us. The goal is always to create dialogue rather than further the distance between us.

On a practical level, that happens through the integration of different people into our social and (especially) professional environments.

Skill #5: Empathy

As we have already established, having an empathetic understanding of the speaker is one of Paul Rogers’ original requirements of effective counseling or, rather, listening.

According to Rogers, empathy is the ability to “perceive the internal frame of reference of another with accuracy, and with the emotional components and meanings which pertain thereto, as if one were the other person, but without ever losing the ‘as if’ condition.”

In other words, empathy is the ability to understand someone’s feelings without fully identifying with them. Even though that part was stated to highlight the importance of therapists keeping a certain distance between themselves and their clients, it should apply to the more average speaker/listener dynamic too.

Namely, as a listener, you have to be able to feel and show a genuine interest in the speaker’s story with the goal of reaching a true understanding of their message and underlying intent.

How can you become more empathetic?

Admittedly, telling people to be more empathetic is a pretty big ask. After all, some people see empathy as a trait we’re born with or, at least, one we max out during our childhoods.

Fortunately, studies indicate that empathy is something that can be learned through coaching, training, and other developmental opportunities.

Of course, approaching the people around us with curiosity is as good of a place to start as any. Rather than rushing to issue a retort or a judgment, we could learn to stop and consider other people’s points of view before responding.

Then again, that is something we could only achieve by practicing mindful communication in our everyday life.

Skill #6: Emotional intelligence

Emotional intelligence is a skill that encompasses several others on this list. After all, it requires us to develop self-awareness, empathy, as well as more general social skills.

Ultimately, emotional intelligence grants us the ability to utilize our other skills with the ultimate efficacy. Such situational awareness allows us to:

- Interpret and reflect the speaker’s nonverbal communication,

- Approach the conversation with the right amount of vulnerability or confidence — whichever is called for,

- Issue validating, questioning, or otherwise appropriate responses, and

- Direct the flow of conversation even from the listener’s role.

An emotionally intelligent person understands the needs of others and is able to answer them without threatening their personal boundaries.

How do you become more emotionally intelligent?

Since emotional intelligence is widely seen as an amalgamation of other social skills, the path to enlightenment lies in the development of the other skills we have mentioned.

Broadening our social awareness, as well as becoming more self-aware, should help. Additionally, learning how to regulate our emotional responses in conversations is bound to improve our communication skills.

Still, if you have zero experience with any kind of self-reflection, we’d recommend therapy or journaling, to begin with.

🎓 Pumble Pro Tip

Developing your emotional intelligence will especially come into play once you start noticing the dips in energy in the people you work with. Fortunately, you’ll also be able to help them bounce back after reading this article:

Skill #7: Critical thinking

Sometimes, no amount of emotional intelligence will allow you to get to the bottom of a problem. If someone is talking about a more convoluted issue, critical thinking could be a more useful tool.

Developing this skill would allow you to follow a conversation while looking for patterns and clues that might require a more objective analysis.

Moreover, it would help you to know which questions are the right ones to ask even (or especially) if you’re unable to discern what someone is talking about in the first place.

Lastly, critical thinking would enable you to quickly and accurately summarize or paraphrase new information, which are crucial active listening steps.

How do you improve your critical thinking skills?

If you want to be able to assess any situation you find yourself in more objectively, you should start by unlearning your subconscious cognitive biases.

Let’s use the well-known confirmation bias as an example.

In essence, confirmation bias is a pretty common mental trap that makes people subconsciously look for evidence to support their preexisting beliefs.

As you can imagine, looking at the world through that lens makes it pretty difficult to keep an open mind when other people are speaking.

And, since the goal of active listening is to properly absorb information, ridding ourselves of biases is key.

Other ways to encourage critical thinking include:

- Learning to recognize subconscious biases in the speaker,

- Researching the topic of conversation beforehand,

- Knowing what you’d like to gain from a conversation, and

- Double-checking the validity of your conclusions before sharing them.

Incorporating these kinds of fail-safes into our thought processes should allow us to examine all available information (spoken or not) objectively.

Skill #8: Memory retention

Lastly, if you want to prove that you’re a good listener, you’ll have to improve your memory retention as well. Sadly, this skill doesn’t come to all of us naturally.

Still, as with the other points on this list, memory recall is a skill we can work on.

In the end, you should be able to recall the main points of a conversation, as well as any ideas the speaker might have shared in your ongoing or previous conversations.

How do you improve your memory retention?

To improve our memory recall skill, we’d first need to deal with the obvious causes of forgetfulness, such as:

- Poor diet and a shoddy sleep schedule,

- Certain medical conditions and medications,

- A lack of physical and mental engagement, and

- Alcohol or drug abuse.

So, ditching any mind-altering substances is a must — as is establishing a healthy diet and sleep schedule. Once we have eliminated those obstacles, we can start actively improving our memory by:

- Playing mind games,

- Taking up new skills (like painting, pottery, or dance),

- Learning to play a new musical instrument (or picking up the one we’d previously abandoned),

- Learning a new language (which can even be done through mobile phone apps or online classes), or

- Practicing recall (by giving ourselves five minutes to remember a bit of information before looking it up).

Alternatively, you can simply write down whatever you deem to be the most important bits of the conversation and refer back to your notebook whenever you need to remember specific details.

Benefits of active listening

People listen for a variety of different reasons. For some, it’s as simple as enjoying the flow of conversation.

Alternatively, as Carl Rogers and Richard Farson put it: “The lawyer […] listens for contradictions, irrelevancies, errors, and weaknesses.”

Yet, even the people who popularized the term ‘active listening’ would say that the skill relies on the listener having an open mind and the goal of:

- Gaining a clearer understanding of other people,

- Providing support and taking responsibility, and

- Furthering mutual cooperation.

While the benefits of active listening will be more or less universal, each of them will have a special draw for certain people.

With that in mind, let’s take a deep dive into the general benefits of active listening.

Benefit #1: Active listening improves communication skills

As Rogers and Farson noted, “sensitive listening is a most effective agent for individual personality change and group development.”

Therefore, the most obvious benefit of active listening is that it changes the way we — and the people around us — communicate.

On the one hand, taking the time to listen intently allows us to take in more information.

If we are confused about something, asking the right follow-up questions allows us to avoid misunderstandings later on.

Even when listening to someone who’s having interpersonal issues, being a reflective listener is often enough to make them resolve their own problems.

So, in a way, having and teaching this skill to others may resolve or even prevent future arguments.

That takes us to the other half of this equation — the changes our attitude can bring about in the speaker.

Knowing that someone is listening attentively to not only your words, but the nonverbal cues you’re sending, has a way of making people more mindful of the way they communicate.

They start to mimic our style of listening even while they’re speaking. They may even clarify their thoughts even before you ask them to.

More importantly, they start to have a more open attitude when other people speak up too.

🎓 Pumble Pro Tip

If you’re looking to boost your conversational skills, you should learn more about what constitutes effective communication. This article should be informative:

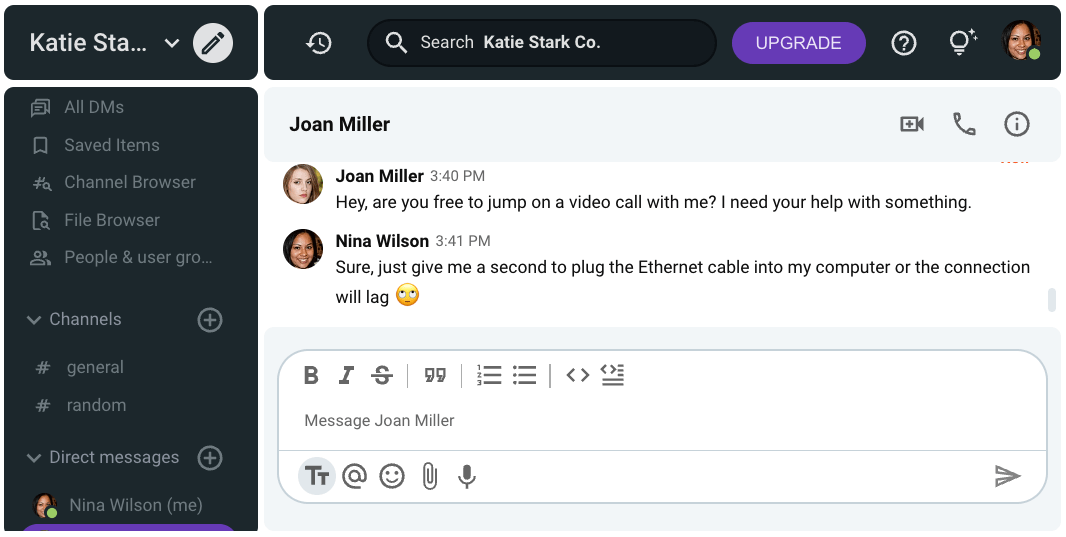

Practice and improve your communication skills on Pumble

Benefit #2: Active listening promotes empathy

We often talk about how approaching people with a positive and empathetic attitude can make them respond in kind.

After all, that is why empathetic leadership is such a successful model of employee guidance.

Of course, you don’t have to be a leader to have a positive impact on the people around you.

In most situations, showing empathy is enough to promote and nurture it in other people.

In the case of active listening, using nonverbal cues and validating feedback to demonstrate your interest in peoples’ stories has a way of encouraging them to speak up more often.

That creates a safe space for the whole group — whether it’s a family unit, a friend group, or even a company — to voice their concerns.

Benefit #3: Active listening increases your understanding of various topics

The ultimate goal of active listening is to understand where the speaker is coming from more clearly.

That requires the listener to be completely engaged while the speaker is talking, analyzing both the content of their speech and the manner in which it was delivered.

As you can imagine, that kind of attentiveness has the obvious benefit of increasing the listener’s level of understanding of the topic that was being discussed.

If we make it a point to approach every interaction with that same level of interest, we could become an expert in a wide variety of subjects.

Being a jack of all trades, in effect, can benefit us in our everyday lives — as well as in the office.

Speaking of which, let’s take a moment to answer a question we have skirted around this whole time: “Why is active listening important in the workplace?”

The benefits of active listening in the workplace

Having established the general advantages of being a good listener, let’s talk about the potential benefits of using active listening at work.

Benefit #1: Active listening creates a positive work environment

Stepping into a more active role when it comes to communication can inspire others in our environment to do the same.

That means that active listening can help us create a culture of honesty and open communication in the workplace.

After all, a positive work environment tends to make people less afraid to talk about their professional hurdles.

Now, in an ideal world, those hurdles wouldn’t have anything to do with members of our own team.

Still, if people on the team disagree, using an active listening checklist as a conversation aid may help us resolve the tension quickly and even improve the whole team’s conflict resolution skills.

Benefit #2: Active listening enables collaboration

Can you even imagine seeing the people on your team listening intently to what everyone else was saying during meetings or brainstorming sessions?

On these occasions, people tend to either completely check out or go to the other extreme of forcing the conversation in the direction they want to see it go.

However, implementing some strategies for active listening could help us improve the whole team’s collaboration skills.

Before you know it, those brainstorming sessions and meetings will look more like team building exercises.

With receptive ears and open minds, everyone will be able to identify and troubleshoot potential problems as soon as they occur, rather than letting them fester and having to fix them later on.

🎓 Pumble Pro Tip

If you’re interested in learning about other ways you might create a more collaborative culture in your company, check out this article:

Benefit #3: Active listening develops better mentorship skills

In addition to deepening your professional relationships in general, active listening can also be a great way to become a better leader, by way of improving your mentorship skills.

Being open to different points of view and knowing how to give feedback are the hallmarks of being a good listener, after all.

So, in effect, knowing how to listen will allow you to see the shortcomings and strengths of the people around you more clearly which will help you coach them more effectively.

On top of that, being an empathetic listener is a great way to inspire respect as a mentor or leader.

It’s one thing to be above someone on the professional ladder, but another to give others the tools they need to climb with you.

Barriers to active listening

Ultimately, active listening at work (and beyond) also requires us to understand the different aspects of the listening process and the various barriers that might hinder it.

Remember, listening comes down to the following actions:

- Perception,

- Interpretation,

- Memorization,

- Evaluation, and

- Reaction.

Each of these stages can be disrupted by different types of barriers, which are usually grouped into the following categories.

Environmental barriers

If we asked people to list some things that might distract them from giving their full attention to a conversation, sensory distractions would probably top the charts.

Of course, background noise and sudden loud sounds are only one part of the problem.

Environmental barriers can also include extreme temperatures, strong smells, and even uncomfortable seating accommodations.

Nowadays, even a poor Internet connection could be considered a significant barrier to communication and, consequently, your practice of active listening.

Essentially, if you find something in your physical surroundings distracting, it’s an environmental barrier you’ll need to work around.

Luckily, most of these issues have relatively simple solutions. If the environment is noisy, you can simply ask your conversational partner to move into another room. Alternatively, you can try to control the noise through other means — such as asking your coworkers to quiet down while you’re in a meeting.

Then again, not every environmental distraction will be as easy to deal with. For example, some sources include the speaker’s negative attitude or ambiguous vocabulary as a potential environmental barrier to listening.

But, since that kind of distraction isn’t something you can affect from your role as a mostly silent listener, we suggest looking the other way if you run into them.

Physiological barriers

Even when our environment is providing the optimal conditions for active listening, there are other disturbances we may have to contend with — namely, internal ones.

The first kind of internal barriers we might experience are physiological distractions, resulting from the permanent or temporary properties of our bodies.

One such property that plagues most of us is the difference between the average speed of speech and our brains’ processing power.

According to some studies, humans are capable of following much faster declamations than those we are usually subjected to. Namely, the average person talks at a speed of 125–175 words per minute.

However, our brains are capable of processing up to 500 words per minute. According to the authors of Communicating at work, that leaves us with plenty of ‘mental spare time,’ during which our thoughts may stray from the conversation.

Physiological barriers also include physical disabilities such as hearing loss or even visual impairments (since many of our conversations nowadays take place over instant messaging apps).

Namely, people with these kinds of disabilities could be left out of the conversation if their accessibility aids malfunctioned.

For example, if someone’s hearing aids aren’t working or they’re sitting in a virtual lecture or meeting that doesn’t have captions, they couldn’t be expected to listen attentively.

Similarly, if a visually impaired person didn’t have access to a text-to-speech reader, they might prefer to use voice messages or jump on a call instead of texting.

Share ideas and updates quickly and effectively over Pumble

Of course, as we have established, physiological barriers aren’t always the result of permanent properties.

Hunger, fatigue, and headaches (or other kinds of physical pain) can also make it pretty difficult to listen effectively.

Psychological barriers

Lastly, we have psychological barriers, resulting from the listener’s mental capacity (and willingness) to listen.

These kinds of internal distractions can be caused by a wide range of factors, including:

- Preoccupation with other (personal or professional) matters,

- Message overload from texting apps, emails, or phone messages,

- Egocentrism (the listener’s belief their ideas are more valuable than the speaker’s),

- Ethnocentrism (cultural ignorance or prejudices that prevent the listener from fully engaging with the speaker), and

- The fear of appearing ignorant (which tends to prevent people, especially in a professional setting, from seeking clarification).

Since this list already mentions ethnocentrism, we might as well include cognitive biases — even though their effect on the listening process can be lessened by developing our empathy and critical thinking skills.

On top of that, the psychological barriers to active listening could also refer to various neurodevelopmental disorders, such as ADHD, dyslexia, or autism.

Alternatively (or additionally), the listener or the speaker could be dealing with mental health conditions (such as anxiety, depression, etc.), which may further affect the communication process.

In fact, any of these conditions could also influence our ability to process speech or focus in more general terms.

Outside of that subsection of psychological barriers, we also need to contend with our established conversational patterns and listening responses.

For example, if we’ve grown used to thinking about retorts while someone is speaking, it can be pretty tough to rid ourselves of that instinct.

Still, if we work to overcome these barriers and create an optimal listening environment, active listening should become a fairly easy exercise.

Active listening techniques and practical application tips

Having gone through the core tenants of active listening, the skills that will help us strengthen that mental muscle, as well as the potential hurdles we ought to look out for, we’re finally ready to break down the active listening process.

Even if the thought of putting all of this into practice seems daunting, everyone should be able to become a more effective listener by following these active listening steps.

Tip #1: Control external and internal distractions

As we have established, there are many barriers to active listening that will get in the way of our practice.

With that in mind, the authors of Business Communication: Product & Process suggest that you’ll want to eliminate as many of those distractions as possible before the conversation takes place.

Thankfully, some of them should be pretty easy to deal with. For example, if you’re unable to concentrate because you’re sitting in an uncomfortable chair, you can move.

Alternatively, if the room smells a bit funky, you can crack a window open or, better still, suggest moving the conversation to another room.

However, some of the internal distractions we’ve discussed may be more difficult to deal with.

Namely, if you’re in physical pain, not being able to focus on a conversation is completely understandable. And the same goes for many of the psychological barriers we’ve mentioned.

Even being in a heightened emotional state could make it difficult to apply ourselves to listening properly.

In any case, if you’re dealing with an obstacle you can’t evade as easily as one might open a window, we suggest postponing the conversation for the time being.

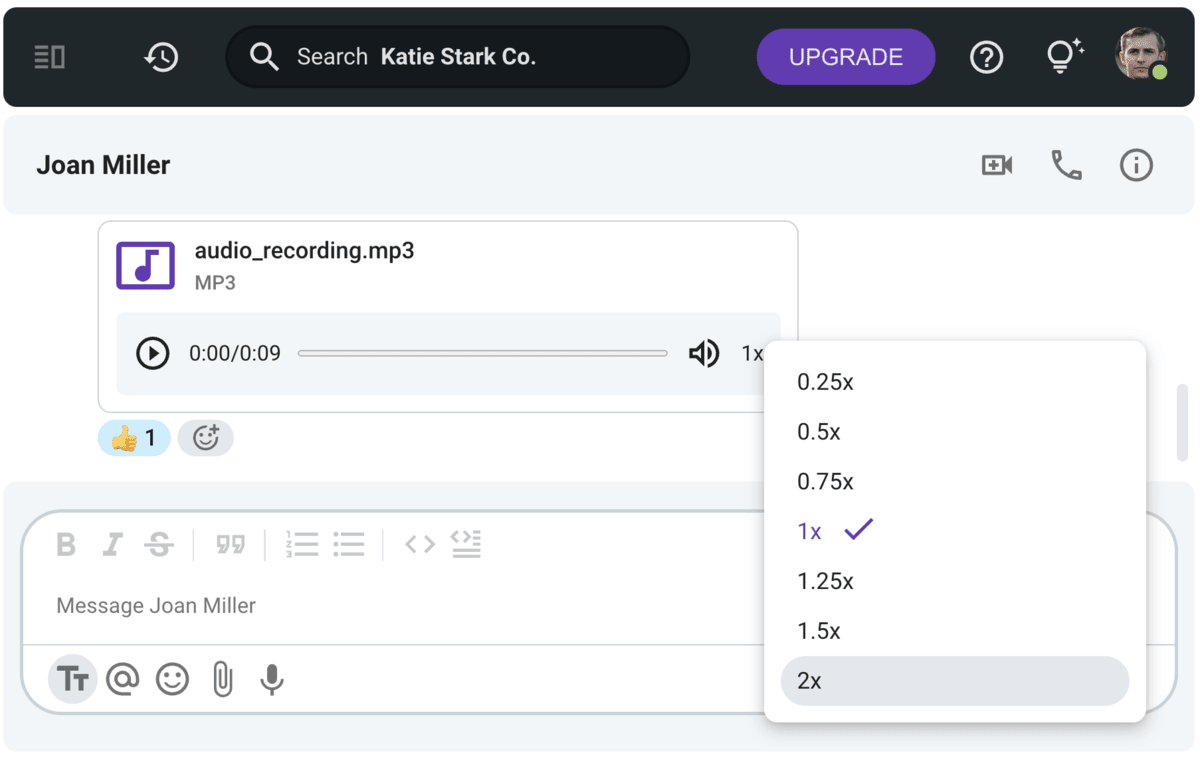

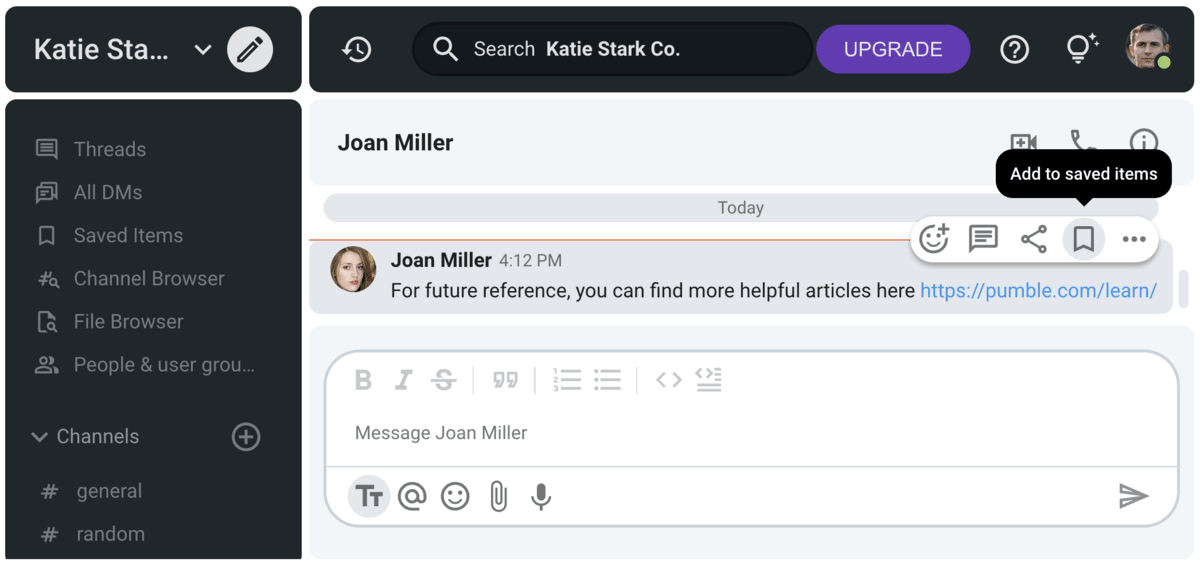

as seen on Pumble, a business messaging app

Tip #2: Take a holistic approach

Before you can engage in a conversation to test out your active listening prowess, you need to get your priorities straight.

Understand that the goal of the conversation and your participation in it is to uncover the speaker’s underlying intent.

To do that, you’ll need to look at all the pieces of information they present to you, which includes everything from the actual content of their speech to their body language — and more.

Furthermore, you should also adjust your attitude and make sure you’re keeping an open mind when it comes to different perspectives.

Ultimately, being self-aware and honest with both yourself and your conversational partners will go a long way toward making you seem like a more approachable listener.

Tip #3: Focus your attention

With your goal in mind, it’s time to get into the active listening mindset. Since this particular exercise requires your undivided attention, you’ll need to put aside any personal concerns and ongoing projects.

When you step into the listener role, it’s important to refrain from:

- Judging the content or style of the speech that’s being delivered,

- Trying to troubleshoot or fix the problem while the other person is speaking,

- Thinking about rebuttals or counterarguments, or

- Interrupting the speaker.

Instead of derailing the conversation by engaging in the aforementioned behaviors, you should do your best to:

- Follow the speaker’s points,

- Analyze the nonverbal cues they’re sending, and

- Keep your body language in check.

Tip #4: Keep track of the unspoken information

If you have taken the time to educate yourself on the subject of body language, spotting it during your conversations with other people should be easy enough.

Gauge the speaker’s mood by taking note of:

- Their posture. Are they slouching or standing stiffly upright? Maybe they’re somewhere between the two extremes. More importantly — do they look comfortable or not?

- What they’re looking at. Are they checking the time on their phone? Are they waiting for a text? Do they keep glancing at someone else in the room while they’re talking to you?

- Their hands and arms. Are they fidgeting or still? Are their arms relaxed or in perpetual motion? If they’re moving, is that because they’re excited, or do they simply come from a more expressive culture?

- Their paralinguistic signals. Does their voice sound different than usual? Are they breathing normally or taking gasping breaths as though they’re rushing to get everything they need to say out?

- Overall body language. Is it more open and relaxed or closed and tense? This could tell you whether the speaker is feeling confident or nervous as they’re delivering their points.

Of course, even with all these clues, you won’t be able to accurately interpret the speaker’s body language without an understanding of their baseline.

Does the speaker usually sway while they talk, or is that a self-soothing behavior they’ve just picked up? Knowing these things will help you see the bigger picture.

Tip #5: Mind your verbal and nonverbal cues

Since we’ve just mentioned some of the things you should keep in mind when examining a speaker’s body language, you should have a pretty good idea of what your own nonverbal signals are communicating.

Essentially, you should:

- Avoid looking at your phone or fidgeting.

- Show your interest by nodding along.

- Keep an open but relaxed body language — elevate your head, relax your shoulders, straighten your back, and face the speaker.

- Encourage the speaker through animated facial expressions, humming agreement (“Mhm.”) and verbalizations like “I see,” “I understand,” and “What happened then?”

If you need to respond, you should also consider the paralinguistic qualities of your speech, taking the time to adjust your tone and use pauses to emphasize important points.

Making sure you’re sending the right message both verbally and nonverbally will go a long way to make you seem like a great listener.

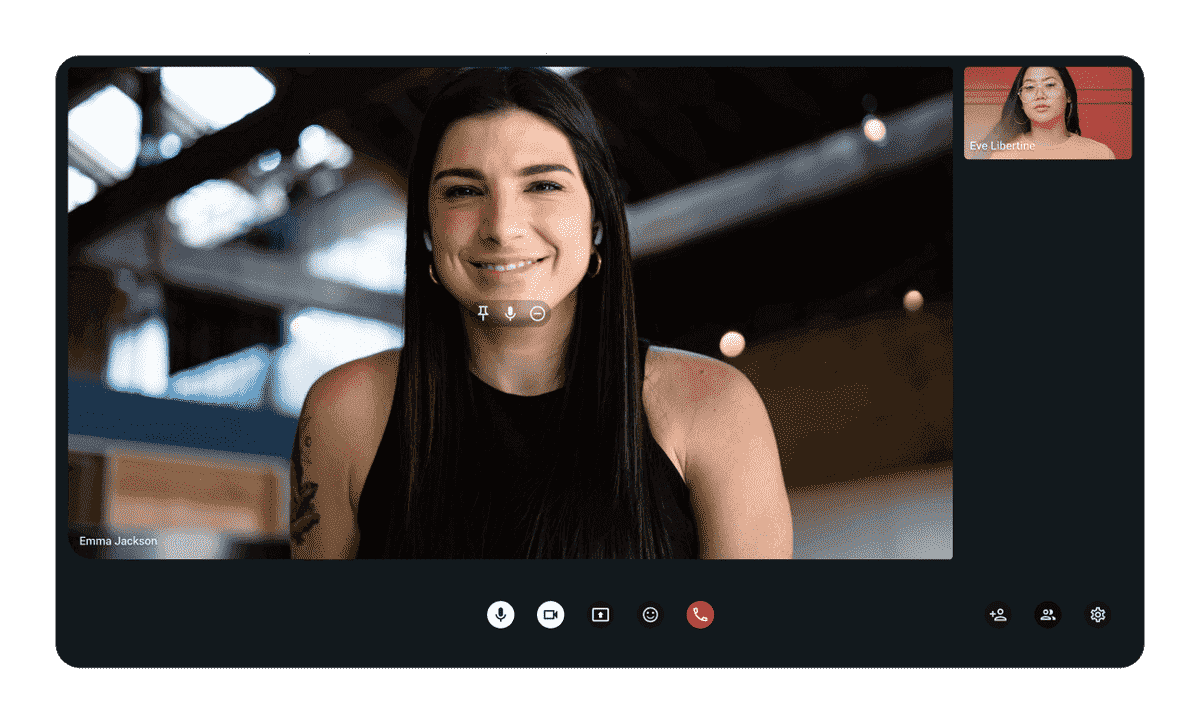

Host effective meetings in Pumble

Tip #6: Sift through new information critically

Ideally, we should make an effort not to judge anything the speaker is saying. However, sometimes, we might need to internally evaluate the information we’re getting from them.

After all, that’s why we have highlighted the importance of critical thinking as one of the crucial active listening skills.

Being able to separate facts from opinions during a conversation can be tricky — especially when we have to listen while simultaneously examining the speaker’s body language and controlling our own.

Thankfully, some speakers make it a point to distinguish facts from opinions while they’re talking. In Business Communication: Product & Process, the authors note that some people use the following statements to preface statements that contain their point of view:

“I think…”

“It seems like…”

“As far as I know…”

“I believe…”

Conversely, many speakers, especially those who aren’t quite as self-aware as they ought to be, try to pass their opinions off as facts. As listeners, we mustn’t automatically accept these statements, no matter how confidently they are delivered.

Tip #7: Retain the information

As we have previously mentioned, retention is a pretty big part of the active listening process.

In addition to helping us gain a greater understanding of the topic that’s being discussed, actively trying to remember different points of the conversation will show the speaker that we are paying attention.

To that end, there are several active listening techniques we can use to keep track of new information while demonstrating our attentiveness to the speaker:

- Stay on track. Make sure you know what the speaker is talking about by saying “Just to be clear…” or “Are we talking about…?”

- Paraphrase certain points. Reflecting the speaker’s statements back to them is a great way to show that we are paying attention. However, it has the dual purpose of making us repeat what we have just heard, thereby increasing our chances of remembering the information.

- Summarize sections of the conversation. If you don’t want to forget the speaker’s previous point when they jump to the next one, make a point of repeating it. Saying something like “Before we move on, I’d like to make sure I understood your previous point. Do you mean…?” should do the trick.

These strategies for active listening will allow you to confirm that you’re absorbing the new information correctly. And, if nothing else, they might help you uncover potential misunderstandings.

Tip #8: Provide appropriate feedback

When it comes to giving feedback, the most important part is determining what constitutes an appropriate response. After all, different occasions call for different responses. Depending on the situation, the speaker might need you to:

- Validate them,

- Empathize,

- Disclose similar experiences,

- Advise them, or just

- Nudge them to keep talking.

After all, different people require different kinds of feedback. While one person may come to you looking for support and validation, another might appreciate a more forthright response.

Even so, there are certain responses that would cause discomfort to almost anyone — such as counterfeit questions. According to Adler’s Interplay, these kinds of questions serve to create tension more than anything else. Examples include:

- Trap questions that require the speaker’s agreement at their own detriment (“You forgot to send the email, didn’t you?”)

- Questions with hidden agendas (“So, I guess you’re free on Saturday morning?”)

- Judgmental questions that point out the obvious (“Are you finally ready?”)

- Questions that require positive judgments (“How do I look?”)

- Presumptive questions (“Why aren’t you paying attention?”)

Sticking to more open-ended questions should put you on the right track, though.

Ultimately, if we want to practice active listening, it would be best not to interject while someone is speaking. Even if there’s a lull in the conversation, we should assume that the speaker is simply gathering their thoughts.

However, if we are called upon to share our insights, we should quickly determine:

- What kind of response the speaker wants to hear,

- What kind of response they would benefit from the most, and

- Which of those two responses would be the most appropriate in that specific situation.

Additional tips for improving active listening at work (with examples)

As we have established, active listening is a crucial skill for anyone looking to build a successful career.

In addition to helping us achieve organizational efficacy, knowing how to listen effectively can also deepen our professional relationships with our coworkers, employees, and bosses.

With that in mind, we wanted to offer some additional active listening tips that might help you use the skill in the modern workplace.

Tip #1: Take notes — or save important messages

As we have previously established, not everyone can be relied upon to memorize the key points of a conversation, especially if they have to keep track of the nonverbal communication of the participants at the same time.

Luckily, writing things down during professional meetings is not only okay — it’s encouraged. So, take advantage of that!

Writing down the main takeaways of work-related meetings will make it much easier to perform tasks. Besides, taking notes also demonstrates your willingness to listen, according to Guffey and Loewy’s Business Communication.

Even so, physical notes may not be the best option for you. In that case, you could take advantage of the tech your company is using.

For example, if the team discussions are taking place in a channel on the company’s internal communication software, you could always save important messages and documents for later perusal.

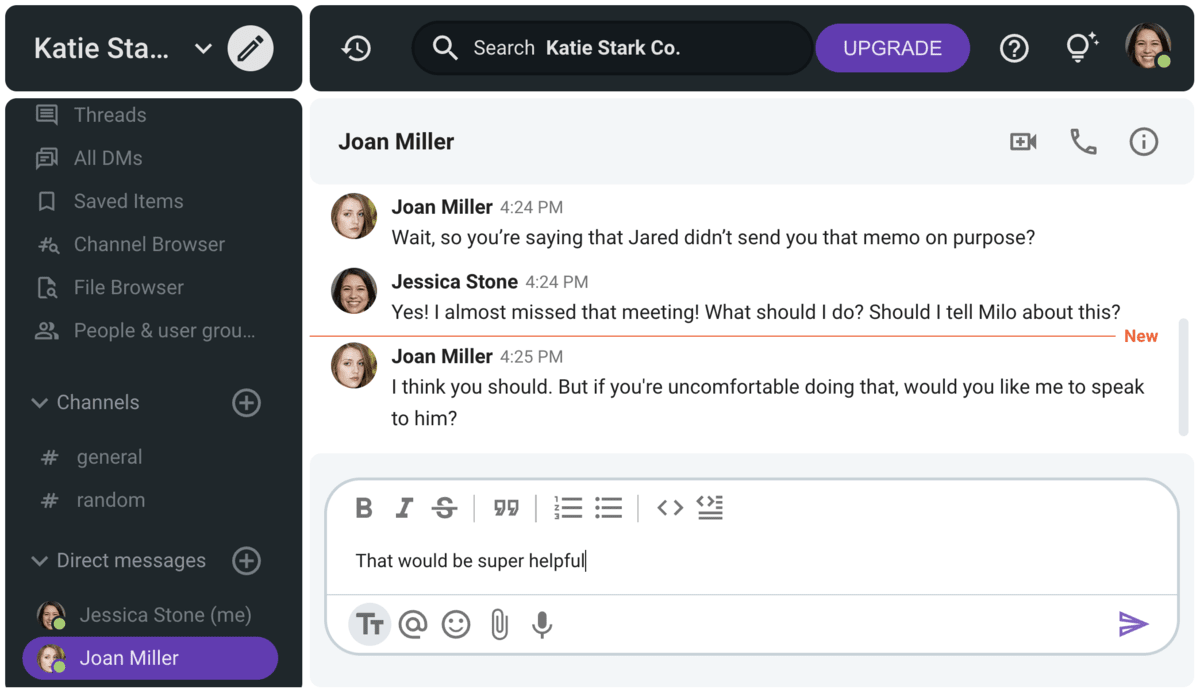

Never miss a conversation with Pumble

Tip #2: Cameras on during meetings

In the past few years, an increasing number of people have transitioned to either hybrid or fully remote work models. As a result, we have all become used to the virtual meeting format.

In the beginning, that meant that everyone was showing up to work meetings in the same way they would have appeared for in-person meetings.

Yet, nowadays, most of us are opting to stay in casual clothing when joining meetings. Unfortunately, for some, that level of informality has also resulted in keeping the cameras off.

However, if that’s how things are at your company, it means that a big part of your active listening toolkit will essentially be useless.

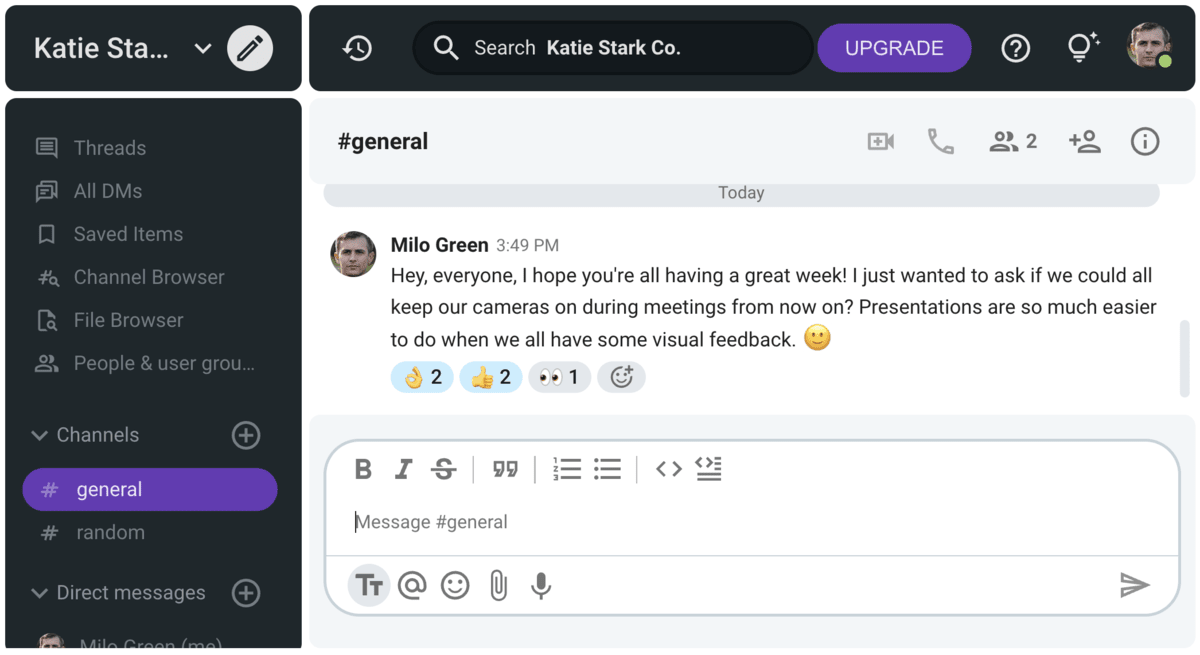

With that in mind, we recommend that you encourage your team members to keep their cameras on during meetings.

Though there’s nothing wrong with turning your camera off if you’re feeling overwhelmed or anxious, that shouldn’t be the norm.

After all, taking the visual element out of our meetings also takes nonverbal communication off the table.

Conversely, keeping the cameras on allows everyone on the team to see and respond to each other as naturally as they would if they were in the same room.

Tip #3: Wait for the other person to finish typing their message before sending a reply

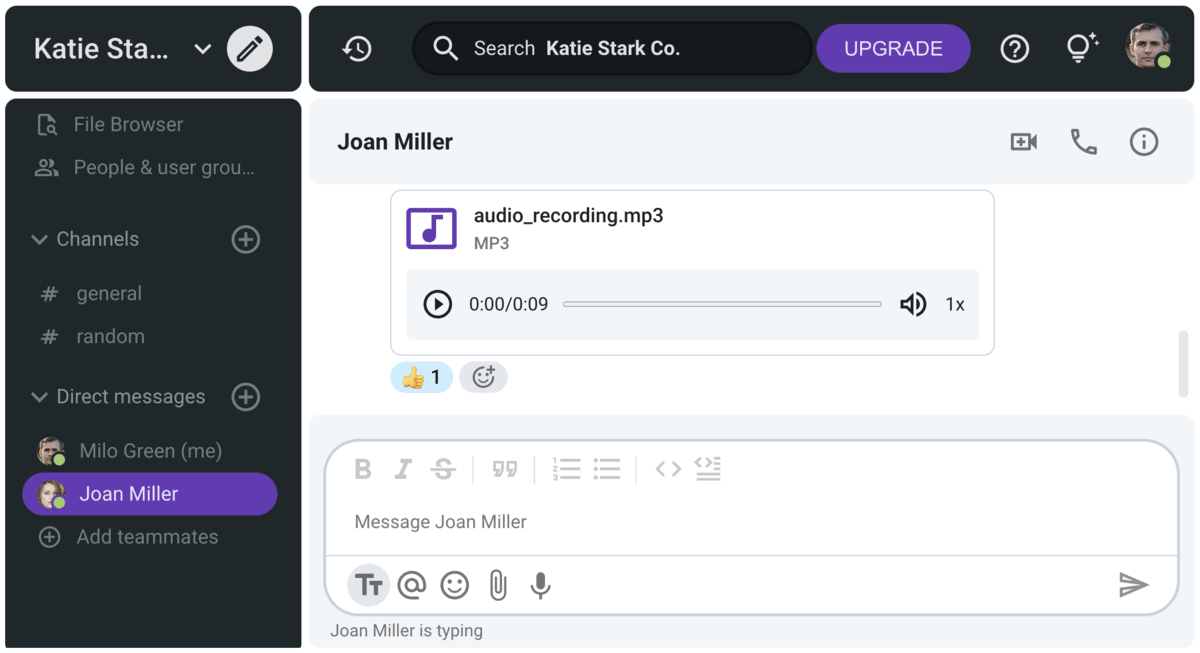

As we have stressed throughout this article, active listening is a skill that can be applied to textual communication, too.

Although you won’t have access to your interlocutor’s body language, you may still be able to figure out their state of mind through their writing style.

However, even if that feature of active listening isn’t available to you — because you don’t know the other person’s usual texting style — there’s still one basic tenant of active listening you can use.

Namely, when messaging other people, you can come across as a great listener by simply not interrupting their train of thought.

So, if you see an indicator that the other person is still typing, give them a few minutes to get their message out before you text back.

Doing so is a great way to demonstrate patience and show that you’re really interested in what they have to say.

Active listening mistakes to avoid

Even though most people rely on their listening skills for pretty much everything — not many are actually good at it.

Whether it’s due to a lack of training, a distracting environment, or one of the other factors we have mentioned in this article, poor listening habits can be difficult to get rid of!

Worse still, most of us wouldn’t know how to accurately grade our own listening skills due to a lack of self-awareness.

If you’re not entirely sure how your listening habits compare to the average person’s, this table should put things into perspective.

| Those with poor listening skills | Those who practice active listening |

|---|---|

| Try to listen while simultaneously performing other tasks | Understand that listening requires their full attention and don’t try to multitask |

| Don’t pay attention because they assume they understand the speaker’s point | Give the speaker the benefit of the doubt and try to follow their story without judgment |

| Only hear certain facts and interesting tidbits | Listen attentively to understand the nuances of the situation |

| Try to take in and respond to everything, especially the speaker’s exaggerations and errors | Listen to understand the main theme or issue being discussed without hijacking the conversation |

| Interrupt with quick retorts as soon as the speaker takes a breath | Allow the speaker to finish talking, then collect their thoughts for a few seconds before responding |

| Shift focus to themselves | Offer support by keeping the focus on the speaker |

| Don’t encourage the other person to keep speaking | Affirm the speaker with both verbal and nonverbal cues |

| Become distracted by the speaker’s grammar, vocal tone, and speaking style | Note the content, not the style, of the message |

| Become distracted by emotional words, have difficulty controlling their own response | Can diffuse overly emotional situations by controlling their response |

| Speak in an aggressive, skeptical, or interrogatory manner | Maintain a calm exterior, understanding that paralinguistic signals are important too |

| Ask leading or presumptuous questions | Ask thoughtful questions to gain a deeper understanding of the situation |

| Offer unsolicited advice, telling the speaker what they “should” do | Wait to be asked before offering a specific kind of feedback |

Enhance active listening with Pumble

Ultimately, using active listening in both private and professional communications is sure to make you a better listener and speaker overall.

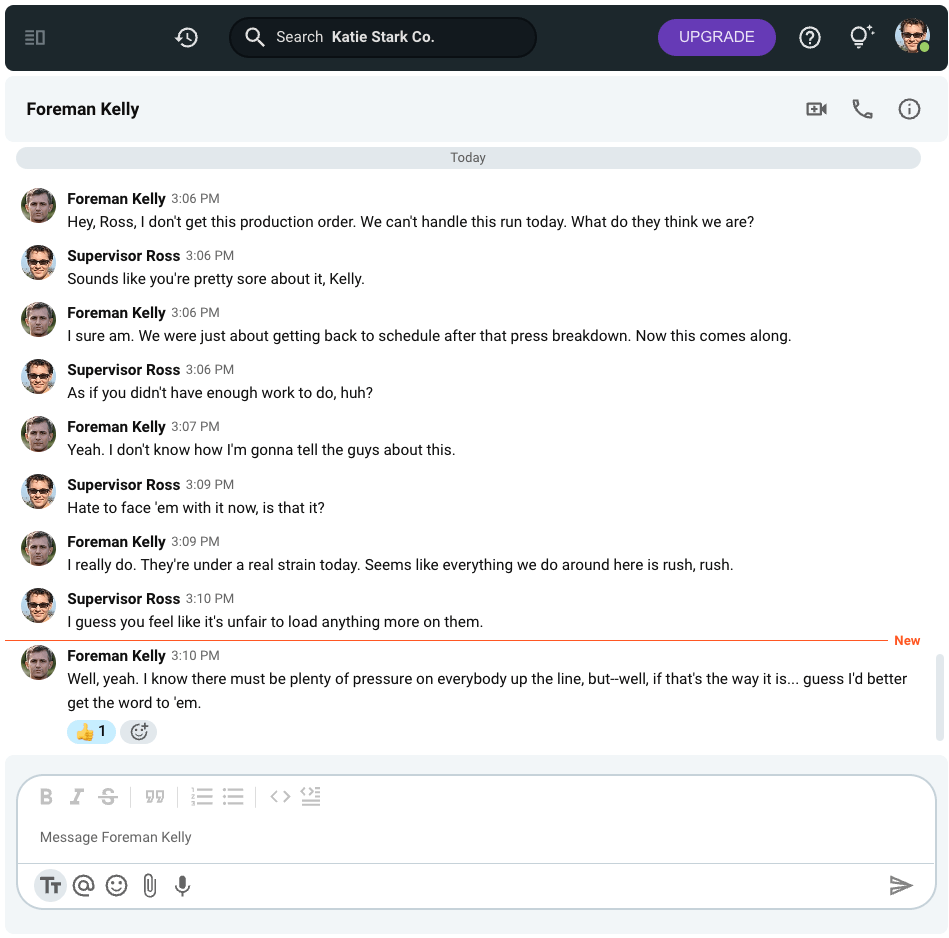

As we strive to become better listeners, it’s essential to leverage tools and platforms that help our efforts. Among them, Pumble stands out as a powerful platform for enhancing communication and collaboration.

As a reliable team communication app, Pumble can elevate your active listening skills to new heights, as its features and seamless integration empower attentive conversations.

Whether it’s through virtual meetings, team discussions in threads, or topic-focused conversations in your channels, Pumble promotes active listening and a culture of empathy and understanding.

How we reviewed this post: Our writers & editors monitor the posts and update them when new information becomes available, to keep them fresh and relevant.