If constructive feedback is the lifeblood of a healthy team, the unfortunate reality is that many teams are anemic.

The staple of a good manager is that they are able to provide productive feedback to their teams, and yet, it seems that team leaders and managers are reluctant to offer any type of feedback, let alone constructive one.

Why?

Well, for starters, they don’t know how.

That’s why today, we’re going over:

- What constitutes constructive feedback,

- The best examples of constructive feedback in the workplace, and

- All the tips on giving constructive feedback to your employees.

Let’s dive in.

- Constructive feedback is a type of assessment that provides employees with specific, actionable advice that helps them improve their performance.

- Even when it’s negative, to be constructive, feedback needs to lift up people and show them you care.

- The best tips for giving constructive feedback are:

- Start with the positives,

- Establish trust,

- Be specific,

- Schedule feedback consistently,

- Build on the positives,

- Be honest,

- Make time for face-to-face feedback,

- Provide context,

- Don’t talk at the employees, and

- Give actionable feedback.

Table of Contents

What is constructive feedback?

Constructive feedback is a type of assessment that provides employees with specific, actionable advice that helps them improve their performance.

Constructive feedback focuses on a person’s achievements and strengths, while also providing suggestions or solutions for areas that might need some improvement.

So, even when it’s negative, to be constructive, feedback needs to lift up people and show them you care.

That sentiment is shared by Dr. Daniel Boscaljon, an Executive Coach and Founder of the Healthy Relationship Academy, which focuses on creating better workplace environments through developing relationship skills:

“The most important way to approach feedback is to recognize that many people are prone to hear feedback as criticism. When feedback isn’t handled well, it can lead to people feeling guilt or shame — even if it was delivered kindly — which can lead to people associating work with feeling bad. Retaining employees means helping them think well of what they do. It means leaving them with a sense of competence. When done well, feedback helps employees feel more confident at doing a good job and more engaged with how they approach their tasks.”

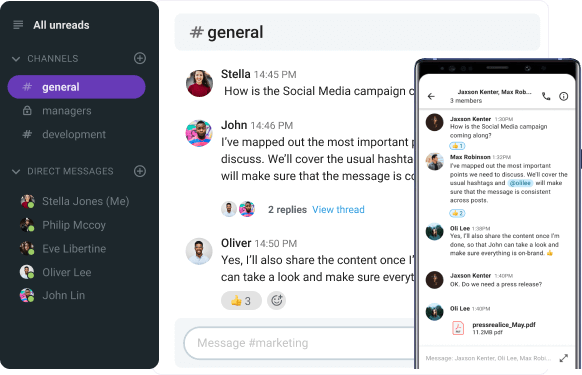

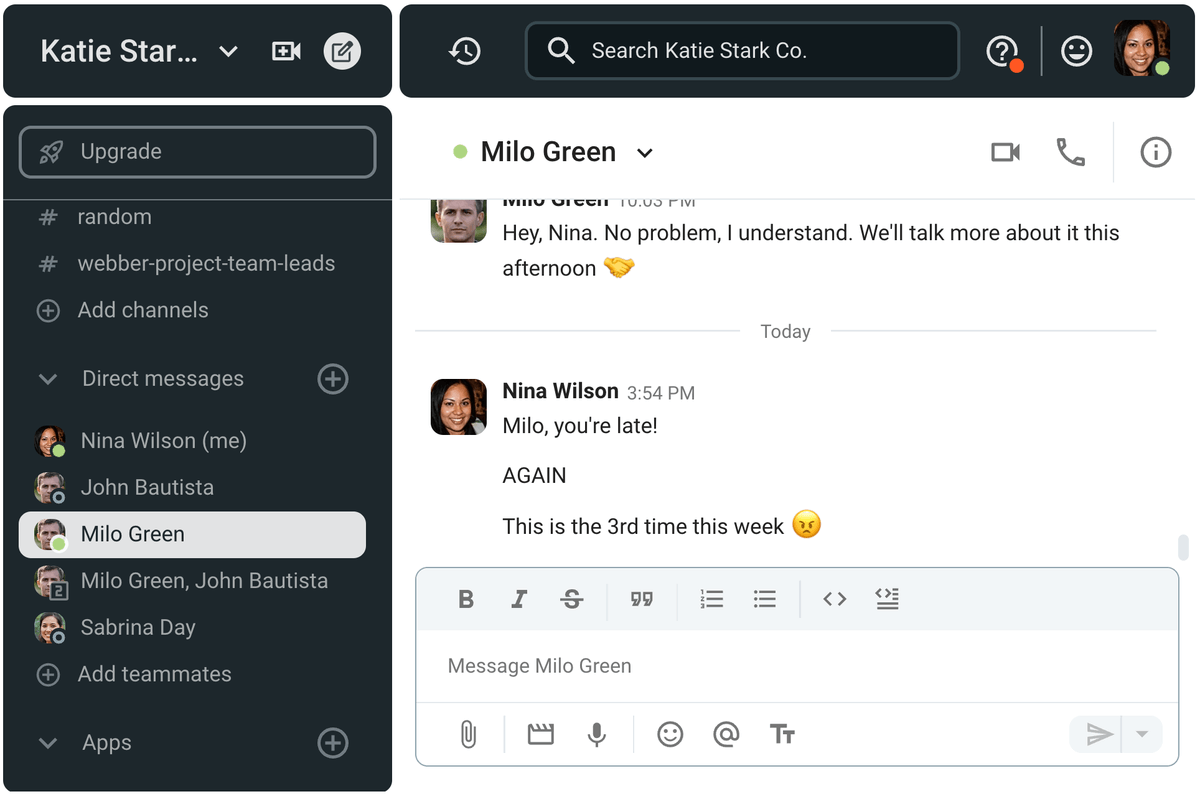

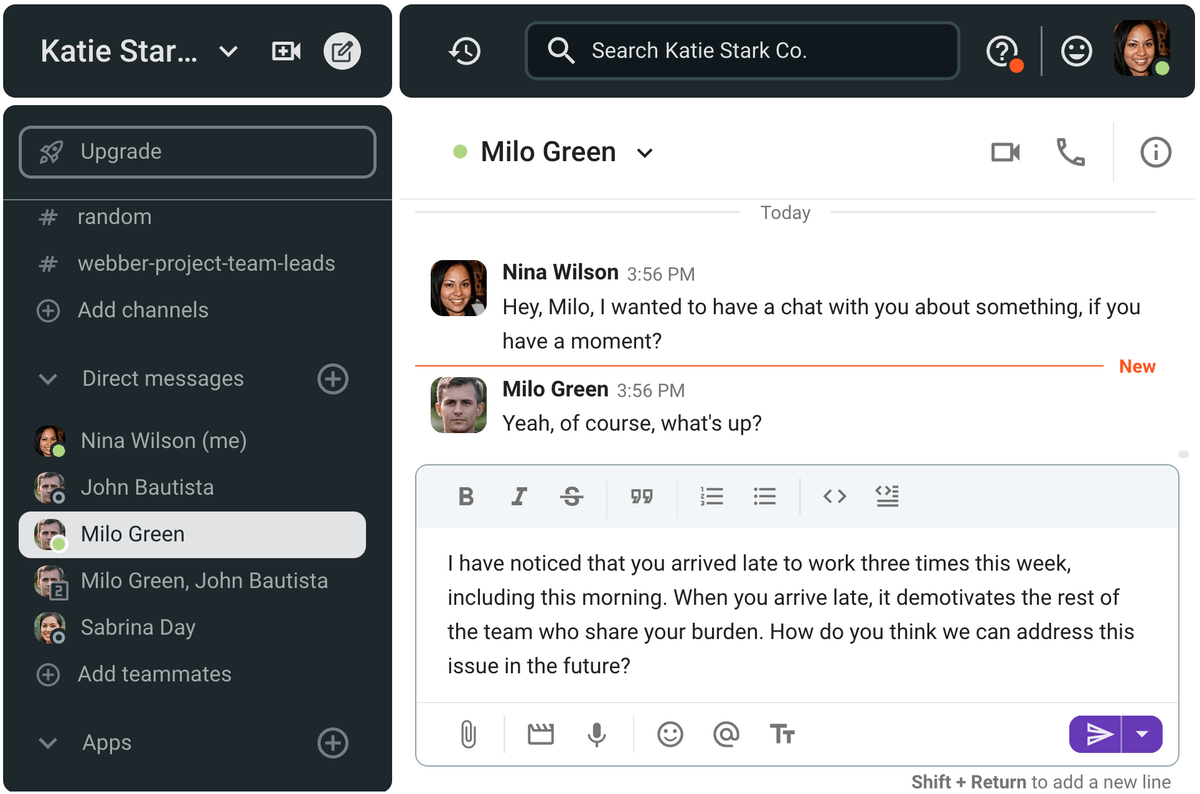

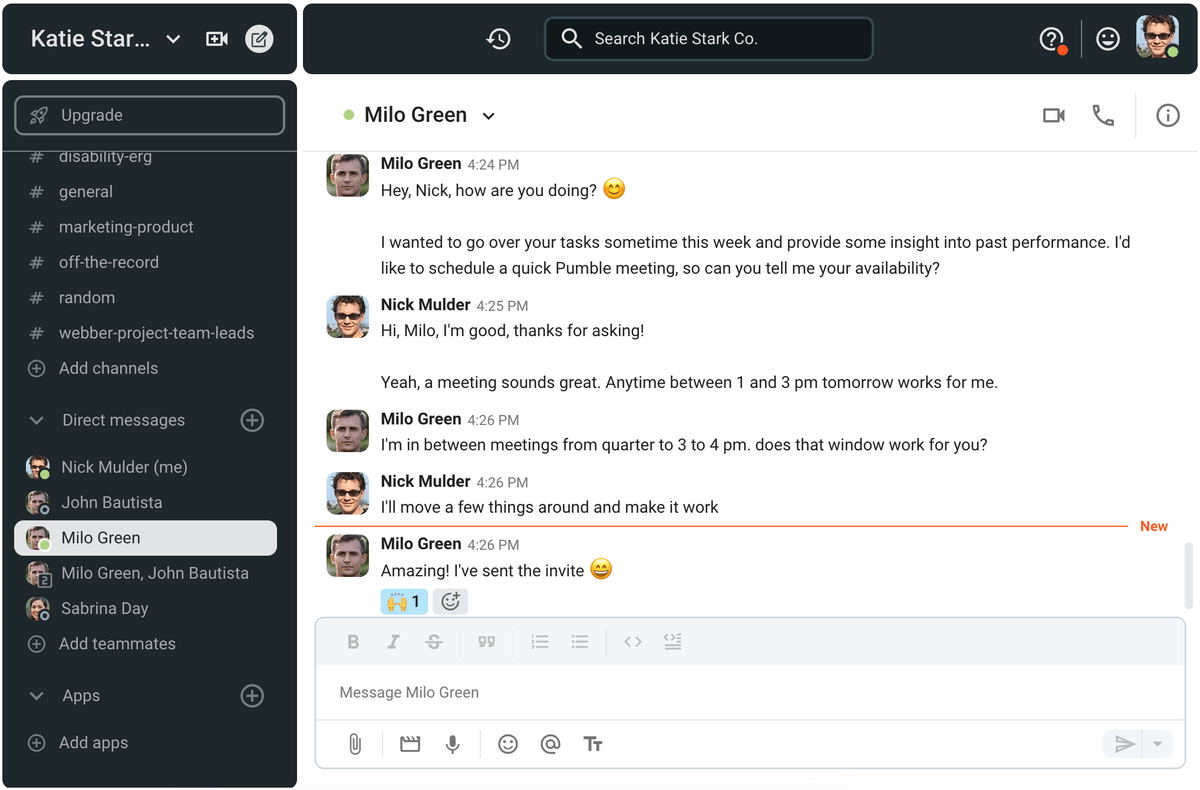

But, what does that look like in practice? Take a look at the exchange on Pumble, a team communication app, that shows a conversation between a project manager and an employee who’s been consistently late for several days.

Now, while the manager did provide feedback, they didn’t do so in the most constructive manner. Take a look at how that exchange could have looked like and see if you notice the difference.

22 constructive feedback examples

According to Pumble’s Communication in the Workplace Statistics, 72% of people believe their performance would improve if their managers were to provide regular feedback.

That’s just one of the many benefits of constructive feedback in the workplace, others being:

- Improved engagement,

- Improved inter-team relationships,

- Boosted morale,

- Effective communication,

- Continuous learning, and

- Improved collaboration.

However, at the same time, only 14% of managers and leaders feel comfortable having feedback sessions, since most of them involve having some type of a difficult conversation.

If you’d like to be a part of that 14% but are unsure where to start, we prepared examples of constructive feedback that you can use in various communication situations at work.

Constructive feedback examples about team communication

To be efficient, a team must have productive team communication. However, that’s difficult to maintain when specific team members are “sabotaging” communication by being poor communicators.

We’ll take a look at 2 different scenarios where you might have to deliver constructive feedback to someone due to poor team communication.

Situation #1: An employee tends to deliver information or opinions in a brutally honest manner.

Constructive feedback example:

“There was a situation last week with Sally, the new intern — you told her her first finished document looked ‘like it was done by someone with no experience.’ I think that was quite harsh, especially since she really has no experience and is here to learn. An encouraging attitude might have been more helpful in that situation, so I wanted to discuss the chances of you working on being a better mentor. Your leadership potential is directly related to your communication skills, so I think you could benefit from some communication courses. You have what it takes to go far in this company and I would like to see that happen.”

Situation #2: An employee tends to “take over” in team meetings and speak over others.

Constructive feedback example:

“Hey, I’ve noticed in several previous team meetings that your eagerness to share ideas and opinions often ends up with you interrupting others. Your ideas are usually stellar and I encourage you to still share them but I’d also like to talk to you about potential ways that you could engage in more active listening in our meetings. That way, you’ll be able to support others in your team and still share your ideas.”

💡 Pumble Pro Tip

Team communication is vital for success, which is why you should always encourage your team members to work on becoming better communicators. To see how you can do that, read the article below:

Constructive feedback examples about time management

The first example we provided in this article dealt with time management. However, an employee being consistently late is just one of many time management-related situations that you might find yourself in.

Let’s take a look at how you might handle the rest of them.

Situation #1: An employee makes deadline-related promises that they consistently break.

Constructive feedback example:

“The deadline for your task on the Perkins project passed yesterday, and I see that you haven’t delivered it yet, so I wanted to follow up with you. When you miss deadlines, you’re delaying not only your task but also the progress of other people who, through no fault of their own, can’t finish their parts. In the future, I’d like you to come to me if you notice that a deadline is too tight or that your workload is too demanding. We can always find a way to work around it or find an alternative solution.”

Situation #2: An employee misses or is late for daily/weekly meetings.

Constructive feedback example:

“I know your tasks keep you plenty occupied and that you can sometimes get lost in your work. Your work ethic is evident in the way you dutifully outperform our expectations, but you need to manage your time better. When you miss a team meeting, you’re hindering other people’s progress, as they can’t move on without your input. Try to be more aware of your schedule in the future, and let me know if there’s any way I can help with that.”

Constructive feedback examples about team collaboration

The backbone of any organization is team collaboration — but only if it’s done right. Sometimes, you’ll find that some team members are more open to collaboration than others, which is when you have to step in and deliver potentially negative feedback to ensure productive team collaboration.

Here are 2 examples of how you might do that.

Situation #1: An employee refuses to share knowledge and help other team members.

Constructive feedback example:

“This cross-functional project we’ve been working on for the past 4 months is vital for the success of our department, and I know your department is depending on it heavily as well. However, I noticed a lack of transparency on your side, which leaves my team tapping in the dark. Would you be willing to share your progress and insights with us and offer more visibility so we can solve problems more effectively? How can we ensure better information exchange between our teams?”

Situation #2: An employee is reluctant to accept a change in protocol.

Constructive feedback example:

“You’ve always been an amazing contributor in a team environment, and your ideas truly stand out every time. However, I’ve noticed that you have a hard time adapting to change, as you have shut down other people’s ideas that proposed a switch in protocol. Can we discuss this in greater detail? I feel like we need to show that we’re team players and encourage every team member to voice their opinions — if nothing else, at least by discussing them before shooting them down.”

💡 Pumble Pro Tip

Having all team members on the same page is just one aspect of successful team collaboration. To learn what the others are, take a look at this article:

Constructive feedback examples about performance

According to Pumble’s Employee Engagement Statistics, 92% of executives believe engaged employees perform better than disengaged ones. And, given that feedback is a powerful employee engagement tool, it’s safe to say you’ll often find yourself needing to provide feedback to ensure better performance.

Here are 2 examples of that.

Situation #1: An employee is consistently failing to meet performance expectations.

Constructive feedback example:

“You’ve been part of the team for a few months now, and I feel like you’re still finding your footing in it, which is why your performance levels aren’t optimal. Your problem-solving skills are excellent and your work ethic is evident, but you’re still unable to meet some of the KPIs in place. I wanted to talk to you about how we could go about fixing that, and what extra help I might be able to offer in that department.”

Situation #2: An employee has trouble delivering at the same level they used to.

Constructive feedback example:

“I’ve always known you to be an excellent worker, so seeing your productivity suffer in the past few months is concerning. I wanted to have a talk with you about the potential causes and how your team members and I can help you overcome them — maybe we can lighten your load or offer assistance of some other kind?”

Constructive feedback examples about lower-quality work

It’s unreasonable to expect all workers to show maximum performance results constantly. In fact, according to an HBR article, constant maximum effort will never lead to maximum results.

However, we can expect employees to perform in a typical way. When that performance falters, we need to give them feedback to ensure they understand where they are lacking, and how to improve in those areas.

Here are a few examples.

Situation #1: An employee’s attention to detail is slipping, which leads to quite a few errors.

Constructive feedback example:

“I’ve noticed a somewhat concerning pattern in your work lately and wanted to touch base with you regarding that. Small errors seem to slip by you more often than before. Now, I know this happens to the best of us but I want to bring it to your attention, as it’s vital we avoid too many of those. I have a short checklist that I go through myself when I do the final review of your tasks, so maybe you’ll find it helpful as well.”

Situation #2: An employee focuses on the quantity of work and fails to meet qualitative expectations.

Constructive feedback example:

“I wanted to reach out to you before our official yearly performance review period rolls around and talk about your output. You’ve been putting in extra hours and, while I applaud your commitment, I need to draw your attention to the quality of the output. I’d like to schedule a meeting with you where we can go over the importance of quality over quantity, so you can get a better insight into why it’s vital that output is at a specific level.”

Constructive feedback examples about boundaries

Boundaries are vital in the workplace because, without them, we risk going into burnout. According to research by Isolved, around 65% of employees feel burned out, which makes them 2.6 times more likely to leave a job.

To mitigate burnout, you must enforce boundaries — both as an employee and as a manager. Here are 2 examples of that.

Situation #1: A manager insists all team members work overtime.

Constructive feedback example:

“Hey, I saw the messages you sent after hours and noticed that you even scheduled a couple of meetings after 6 p.m. Unfortunately, I won’t be able to attend those, as my working hours are 9–5. I’m doing my best to maintain a healthy work-life balance, and can’t compromise the progress I’ve made so far. I understand that you’re under pressure to meet the deadlines and that the meetings need to happen ASAP, so, if you’d like, I’ll share the times I am available, and we can reschedule them.”

Situation #2: An employee works overtime and risks burnout.

Constructive feedback example:

“I admire your commitment to your job, but I wanted to let you know that you don’t need to work overtime. You have set working hours for a reason, and you should enjoy the rest of your day and not worry about work. As a company that prides itself in maintaining a positive workplace environment, we encourage all our employees to set clear work-life boundaries.”

Constructive feedback examples about attitude

Attitude is a vital factor in the way we convey information, according to several communication models. It can help us make our communication more transparent.

However, people’s attitudes can also lead to negative communication and hinder our efforts to establish effective communication in the workplace.

Let’s see how we can address attitude when giving constructive feedback.

Situation #1: An employee demonstrates a negative attitude in team meetings.

Constructive feedback example:

“Hey, I wanted to check in with you because I noticed some behaviors that are unlike you. You’re really abrasive when communicating with other team members and me during team meetings, and I wanted to check to see if there’s something in particular that’s making you unhappy. Do you not enjoy the team dynamics? Or, perhaps you feel the meetings are unhelpful? In the future, I’d appreciate it if we could solve any issues that arise before they spill out in this manner — you can always knock on my virtual door and voice your complaints.”

Situation #2: An employee is rude toward other team members and staff in the office.

Constructive feedback example:

“I’ve noticed that your attitude has become quite negative and sometimes even rude in the office. It’s important that we curb that type of thing because it can spread quickly as well as affect other people and their performance. So, I wanted to touch base and see what I can do to help you out.”

Constructive feedback examples for a colleague

Providing feedback is a staple practice of good leadership — and since not all leaders are managers, you might find yourself giving feedback to your colleagues.

Here are a couple of examples of how to provide constructive feedback to colleagues.

Situation #1: A coworker isn’t a team player.

Constructive feedback example:

“We’ve worked together on quite a few projects in the past, but lately it seems like you prefer working in isolation, which leads to an overlap between your efforts and the efforts of myself and other team members. What do you think about instituting a check-in meeting or another type of meeting every week, where we can go over everyone’s progress? That way, we can avoid doing double work in the future.”

Situation #2: A coworker often delegates their tasks to other team members.

Constructive feedback example:

“Hey, I noticed I’ve been tagged as the assignee in our Pumble team channel for several tasks that used to belong to you. I am currently at capacity and have a lot on my plate, so I can’t take them on. However, if you’re struggling, I can help you talk to our manager about redistributing your workload. In the future, I’d appreciate it if you’d give me a heads up before just delegating your work to me.”

Constructive feedback examples for a manager

Finally, just because you aren’t in a leading position doesn’t mean you shouldn’t provide feedback. In fact, managers can often also benefit from receiving feedback, so let’s take a look at the 2 examples of how you can provide some feedback to your higher-ups.

Situation #1: An employee gives feedback to their manager about an uncomfortable situation they put the employee in.

Constructive feedback example:

“Hey, I wanted to talk to you about the situation we had this morning in the lounge. While I completely agree with you that I made a mistake in handling the data for the Percey project, it made me uncomfortable that you raised that issue over morning coffee in front of everyone. In the future, I’d appreciate it if you’d come to me privately first.”

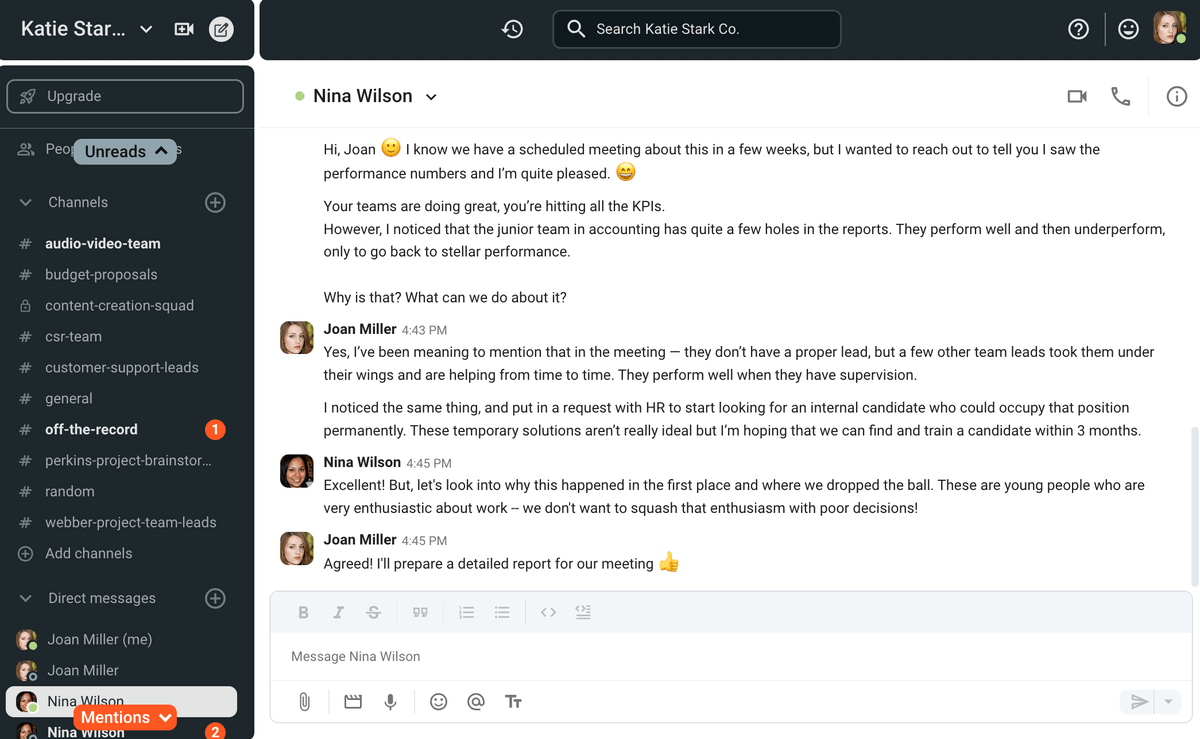

Situation #2: A leader gives feedback to a manager regarding the poor performance of their team.

Constructive feedback example:

“Your team’s performance didn’t meet expectations in this quarter. Of course, I fully understand there are a lot of contributing factors there, but, as the leader of the team, the responsibility falls on your shoulders. So, I was hoping we could go over the numbers together and you can help me understand what happened. That way, we’ll be able to pinpoint exact issues and make a plan for the future.”

Tips on giving constructive feedback

While our examples of how to give constructive feedback in the workplace might be helpful to you every time you find yourself in those specific situations, it’s also good to know how to give effective feedback in general.

That’s why we prepared this list of tips on giving constructive feedback for managers, leaders, and all of you who are in the tricky situation of having to articulate some observations to your employees.

But, before we delve deeper into the 10 tips, we’d also like to give you a sort of pre-tip — prepare yourself.

Giving feedback isn’t an easy job, even if the feedback is positive. And, as one of our contributors, Elena Sarango-Muniz, a Leadership Coach, HR Consultant, and Speaker, says, mental preparation is crucial.

“I always recommend that before feedback is given, the feedback giver should prepare mentally, and be at peace with what they are about to tell the other person or team. One way to do this is to ensure that the feedback about to be given is necessary and will make things better for the employee, team, and organization. The main purpose should be a positive one.”

Tip #1: Start with positive feedback

And, speaking of positivity, our first tip is aimed at beginners and it has everything to do with positive feedback.

If you’re just starting out in a management position and you’re about to provide feedback for the first time, practice with positive feedback.

As Dr. Cindy Goodwin-Sak, the creator of Valiant Leadership, a company that helps organizations build more productive teams by creating great leaders, noted, it’s vital that you start small — and by that, she means start positive.

“There are many feedback models, but they’re largely the same. They identify a specific behavior or action and the resulting outcome. The behaviors can be challenging to identify for beginners. My top tip is to stick to positive feedback while you’re learning how to separate behaviors from judgments.”

Tip #2: Establish trust

If you’ve found yourself on the receiving end of “negative” feedback and thought to yourself, “Oh, that’s it — I’m definitely getting fired now.” there might be a lack of trust between you and your employer or manager.

We are more open to feedback from sources we trust. Effective feedback builds trust on its own, but sometimes you need to kickstart the process.

So, to ensure your feedback is well-received, you need to build trust in your team through various practices, including team-building exercises. Team building can strengthen the bonds between you and your team as well as those between team members.

Of course, other methods — such as practicing transparent communication or even overcommunication — will also lead to your team members placing their trust in you and being receptive to feedback.

💡 Pumble Pro Tip

If you need some fresh ideas about which team-building exercises might help you improve communication and trust in your team, read the following article:

Tip #3: Be specific

Arguably the most important aspect of constructive feedback is its specificity.

Vague feedback achieves nothing other than discouraging the employee, as noted by Kristen Fowler, SHRM-SCP and Vice President of Human Resources and Recruiting at JMJ Phillip Group.

“Be clear and concise and tie the feedback directly to the employee’s goals. Avoid general phrases like ‘You aren’t meeting expectations’ or ‘You need to improve’, with no further guidance. Set clear and specific actions you would like to see from the employee — for example, ‘I noticed you are struggling to hit your daily reach-out goal, have you tried shifting your schedule back an hour to see if your response rate improves?’”

Tip #4: Schedule feedback (and be consistent with it)

Feedback isn’t a “spur of the moment” thing. You should schedule it and deliver it consistently — otherwise, it will be disruptive and unconstructive.

Disruptive feedback takes the form of unannounced feedback. Remember — for all the benefits of feedback, it’s still not a process employees enjoy. For this reason, it’s better to schedule feedback ahead of time.

Studies show that it takes employees approximately 23 minutes to refocus after suffering through distractions. Should the feedback be received negatively, the consequences are likely to be even more impactful.

As for unconstructive feedback, this generally occurs when managers feel that anything is better than nothing. In extreme cases, this can lead to micromanaging, which is known to stifle creativity and even increase the rate of employee turnover.

If you’re struggling to separate constructive from unconstructive feedback, our contributor, Elena Saango-Muniz advises that you ask yourself why you’re providing feedback.

“[What separates constructive and unconstructive feedback is] the ‘why’ behind it. If the reason you are giving feedback is so the individual learns and becomes a better person, worker, professional, or leader, then it is constructive. If the feedback being given is so the person feels bad, quits their job, or makes things worse for them, it is not constructive. Sometimes it will take a while for the receiver of the feedback to realize the benefits of the feedback given to them, ultimately, well-meant feedback will always reap positive effects on the receiver, even if it takes years.”

Tip #5: Build on the positives

If you’re finding it hard to deliver constructive criticism in a non-discouraging way, might we suggest starting with the positives and building on them?

Building on the positives means having a strategy where you connect the critical feedback with the positive feedback and elaborate on how improving the former will also positively affect the latter.

For example, let’s say John is excellent at his job, but not the best when it comes to team communication. You could approach giving him feedback like this:

“I am consistently impressed by how quickly you’re able to fix bugs without any drop in quality. But, when you don’t coordinate your efforts with the rest of the team, much of your effort gets wasted. How do you think we can find a strategy that will help you communicate the pace of your work with the rest of the team so that none of our efforts go to waste?”

This lets you frame the entire conversation in a positive light and communicates your well-meaning intentions along with the need for change in behavior.

Tip #6: Be honest

If you’ve decided to utilize the previous tip, always keep this mantra in mind — honesty is the best policy. What’s more, honesty should be the staple of your leadership communication style.

Leaders who are too fearful of upsetting their employees can quickly fall into the trap of overplaying the positives and barely touching on the negatives.

Overexaggerations, euphemisms, sugar-coating, and beating around the bush don’t benefit anyone.

So long as your feedback is honest and your good intentions are transparently signaled, there’s not a lot more you can do to soften the blow without trespassing into the territory of counterproductive results. And that’s exactly what dishonesty is — counterproductive to constructive feedback.

Tip #7: Make time for face-to-face feedback sessions

Feedback should always be delivered face-to-face. This can pose a particular challenge for managers and leaders of remote or hybrid teams who mostly rely on written communication.

Still, no matter the circumstance, you should make time for a face-to-face feedback session with your team members — be it in person or via a video call.

While they are unable to convey the full breadth of non-verbal cues, video calls still help us regain some semblance of control over how our feedback will be interpreted. Video also lets you monitor the emotional state of employees on the receiving end of feedback.

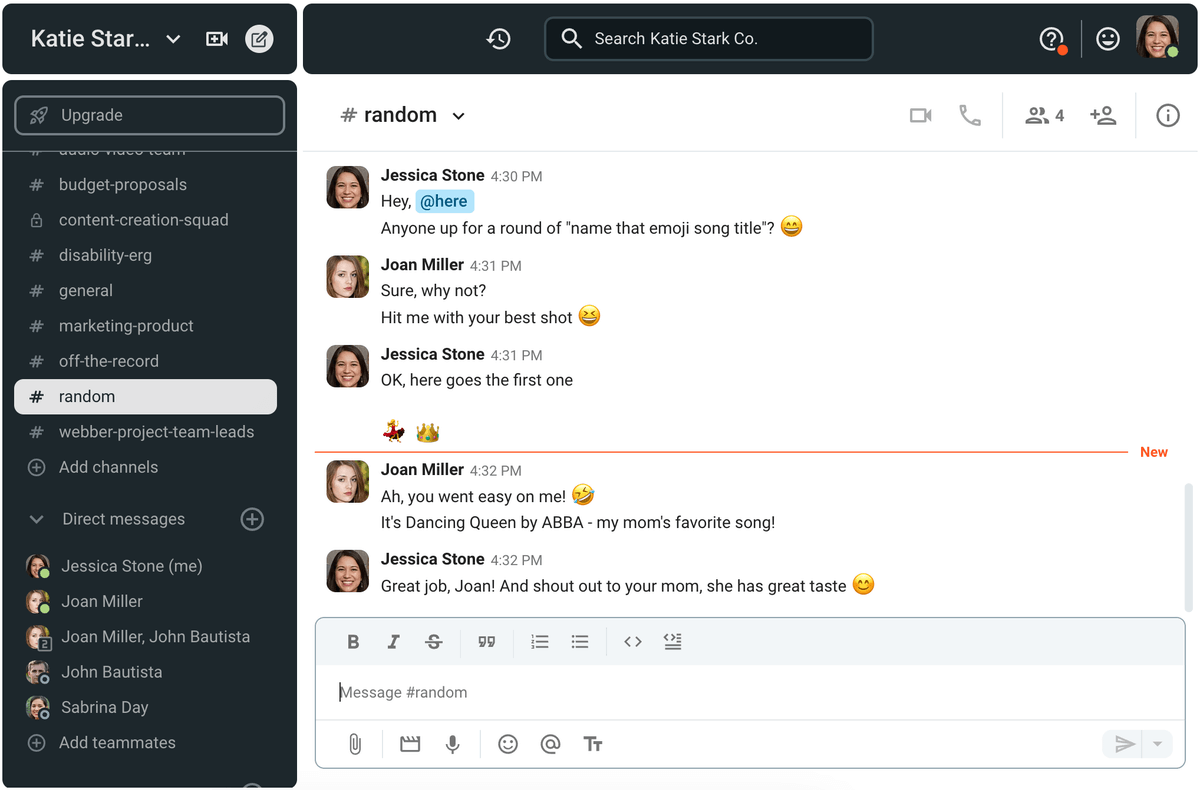

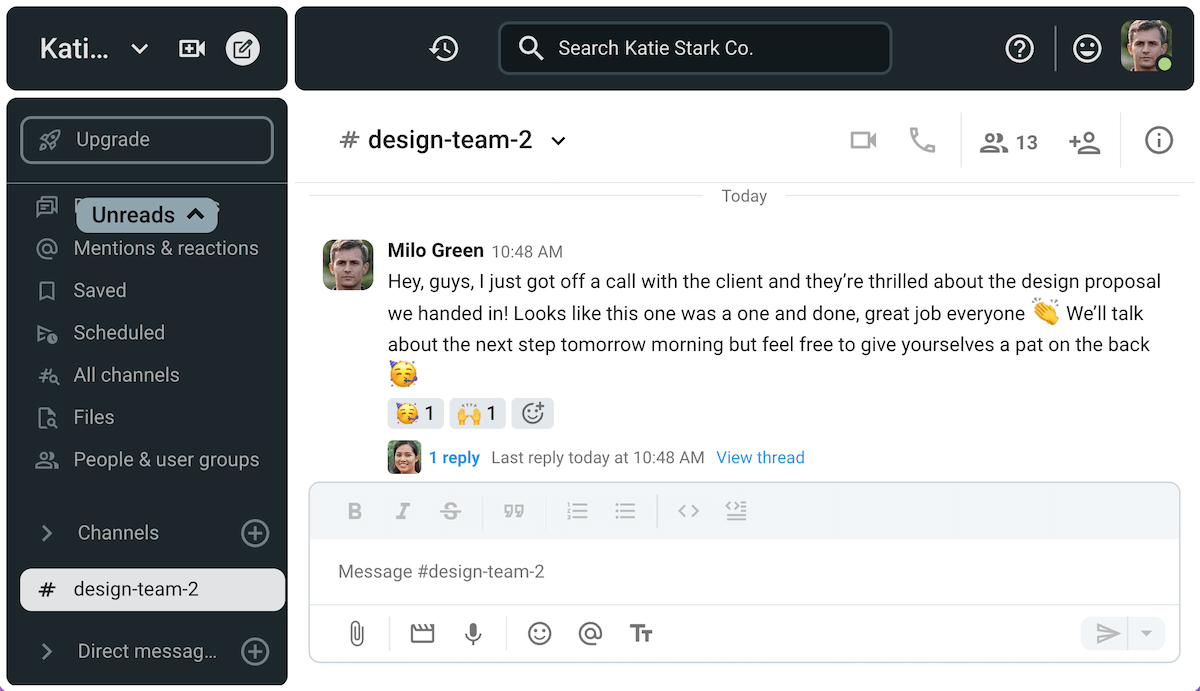

On the other hand, positive feedback (i.e. praise) can be communicated via text. For example, remote teams can utilize a business messaging app like Pumble to celebrate success and acknowledge a job well done — as shown in the image below.

Still, when it comes to critical feedback, remember that removing non-verbal communication can have devastating effects on the reception of feedback. Non-verbal cues like facial expressions, posture, eye contact, tone of voice, and gestures all help us zero in on the intended meaning.

Effective communication is all about mutual understanding, and non-verbal cues help us both convey meaning and understand it more clearly.

Tip #8: Provide relevant context

If you’re not upfront about the context surrounding the feedback, you’re inviting misunderstanding. Implicit understanding should never be assumed.

So, be clear about why you want to provide feedback — otherwise, for all you know, the employee may think they’re being called for an entirely different reason.

For example, if there’s an employee who keeps interrupting others during conference calls, don’t ask them “What’s your problem?,” or “Why have you always got to jump into other people’s sentences?”

Instead, be specific: “I noticed that you kept interrupting Lisa (Behavior) during her presentation yesterday (Situation).” This way, instead of inviting vague or defensive answers, like “What problem?,” or “I don’t always interrupt,” you establish a precise context.

We spoke to Melissa Miller, the Co-Founder and COO of Tandem, a company that helps teams achieve a high-performance culture through continuous feedback. She offered a quick checklist that can help you provide context when giving feedback.

“The best feedback requires thought and effort. Think through these things when crafting constructive feedback:

- What exactly did they do? No, even more specific than that.

- What was impressive? Name the impact.

- What would you like them to do again? Encourage more of this.”

💡 Pumble Pro Tip

Not providing enough context often leads to miscommunication. To learn how to avoid it, read our blog post:

Tip #9: Don’t talk AT employees

Feedback is a form of two-way communication — a dialogue, if you will. Both parties need to be involved.

The best way to facilitate two-way communication while giving feedback is by sharing the responsibility for finding the solution.

Ask the employee whether they have any ideas for how to resolve the relevant issues. They’re capable people, that’s why they were hired.

Also, don’t assume to know what the reasons for their behavior are — perhaps that person who keeps cutting in during conference calls isn’t rude, but they simply have a laggy internet connection.

Tip #10: Give actionable feedback

Accepting constructive feedback in the workplace is as hard or harder than giving it. That’s why we have to ensure all feedback we provide is actionable — otherwise, people won’t be receptive to it.

To keep your feedback actionable, it helps to create a plan of action by asking yourself the following questions:

- “How and when have I observed unwanted behavior?”

- “What examples can help to clearly communicate my observations?”

- “What consequences do I see this type of behavior leading to?”

- “How can I approach the problem in a way that will help the employee?”

- “How do my emotions influence the overall equation?”

Once you can find the answers to these 5 questions, you’ll be ready to provide feedback that’s truly constructive and actionable.

The idea is to aim your criticism at the employee’s behavior, rather than at the employee. This will directly increase the chances of your actionable feedback actually leading to learning and appropriate results, as noted by Cindy Goodwin-Sak:

“The key component of constructive feedback is that the recipient can learn about the impact of their positive and negative behaviors. Positive constructive feedback reinforces the behavior and positive outcomes of behavior you want to see repeated, while negative constructive feedback helps correct the behavior to something more desirable.”

Make your feedback even more constructive — with Pumble!

As evident, giving constructive feedback in the workplace isn’t easy, but it’s a necessity for a thriving team.

The way you compose and deliver feedback can make or break not only the relationship with the recipient but also their performance and attitude towards work.

The tips and expert advice offered in this article can help you compose the perfect constructive feedback, while Pumble, a team collaboration app, can help you deliver it.

With Pumble, you’ll be able to:

- Craft feedback drafts in your Pumblebot text window or in your personal chat,

- Send positive feedback via direct messages, public and private channels, or group messages,

- Invite team members on 1-on-1 meetings and feedback sessions, and

- Schedule feedback sessions directly in your calendar.