Even at the best of times, quality communication is one of the key prerequisites for a successful work process.

However, its importance increases exponentially in times of crisis. Whenever an unexpected negative event impacts an organization, the quality of subsequent communication greatly determines the organization’s perception and reputation — both externally, in the public eye, and internally, among its team members.

Rather than hoping that the stroke of misfortune will avoid them, organizations need to be prepared for such an eventuality.

In this article, we will focus on internal crisis communication — how organizations communicate with employees during a crisis. We will define the basic related terms and highlight the best practices for internal crisis communication that ensure that internal stakeholders have all the relevant information on time.

Let’s dive in!

- Crisis communication is comprised of the systems and practices a company uses to protect its operations and reputation when faced with unexpected events and potentially disruptive events.

- We recognize 2 types of crisis communication — public crisis communication, aimed at the public, and private, which comprises the messages towards employees.

- Some tried-and-true crisis communication strategies include acting promptly, using relevant communication channels, crafting a crisis communication plan, and providing employees with crisis communication and management training.

- Other effective practices organizations can adopt include avoiding silence and censure, sticking to the facts, remaining consistent, supporting the workforce, collecting feedback, and reflecting on the experience.

- Although many types of crises are hard to predict, preparing in advance can help soften the blow and assure employees the organization is moving forward with integrity.

Table of Contents

What is crisis communication?

Crisis communication refers to the strategies, protocols, techniques, and systems organizations use to overcome threats to their reputation or overall business dealings.

Timothy Coombs, the author of the Situational Crisis Communication Theory, defines crisis as “the perception of an unpredictable event that threatens important stakeholder expectations, significantly impacts the organization’s performance, and/or creates negative outcomes.”

Additionally, Coombs describes crisis communication as “the body of messages created to address the crisis.”

These descriptions bring us to a broader definition of crisis communication as “the collection, processing, and dissemination of information required to address a crisis.”

However, Coombs doesn’t stop at merely defining this concept — he also goes on to identify two main types of crisis communication.

Crisis communications: The two main types

Based on the different groups of stakeholders it addresses, Coombs recognizes:

- Public crisis communication: It includes messages (words and actions) aimed toward external stakeholders (investors, customers, suppliers, the general public, etc.).

- Private crisis communication: It includes messages exchanged between the members of the crisis team and private communication towards the employees.

It’s important to note that employees are a specific group of stakeholders, as they are the audience for both public and private crisis communication.

Ideally, private and public crisis communication should be consistent and homogenous, relaying the same messages both internally and externally.

While there is always a certain amount of overlap between public and internal crisis communication, we will focus on the latter — assessing how to best communicate with employees during and immediately after a crisis.

Crisis communication strategies

In the book Crisis Communication Strategies, author Amanda Coleman examines several effective practices, which include:

- Moving quickly,

- Using the appropriate communication channels,

- Creating a crisis communication plan, and

- Offering crisis communication and management training.

We’ll delve deeper into each of the above points to understand why these strategies matter during a crisis.

#1: Moving quickly

When taking crisis communication steps to minimize disruption, time is of the essence.

Putting off communication with employees during a crisis can result in a time delay that causes:

- Uncertainty,

- Fear, and

- Distrust.

For this reason, it’s necessary to make decisions quickly and notify the workforce of what will occur in the coming period.

While it’s critical for leadership to act quickly, their endeavors shouldn’t appear rushed, as if very little thought has gone into them.

One of the ways businesses can avoid this pitfall is by identifying the best communication channels for crisis communication management.

#2: Using the appropriate communication channels

Communication channels facilitate the successful exchange of information. When navigating a crisis, one question to keep in mind is: “What’s the best way to keep the workforce in the loop and collect input?”

In some situations, the CEO may decide to hold an all-hands meeting to explain the situation the organization has found itself in. But, others might want to share documents with their teams to ensure everyone can follow how the situation unfolds and pitch in with their ideas.

Regardless of which communication channel the business has decided to rely on, the tool should help distribute a comprehensive crisis communication plan.

💡 Pumble Pro Tip

For more information on different channels of communication, including their pros and cons, head to this detailed guide:

#3: Creating a crisis communication plan

One of the most important steps in crisis communication is crafting a plan of action.

Once the crisis is resolved, how well the business dealt with the circumstance and the effectiveness of their communication will be scrutinized.

Here’s where the crisis communication plan kicks in.

The plan should be simple but leave enough room for flexibility so that businesses can customize it to address the specific nature of the crisis.

Instead of stuffing the plan with excessive detail, it’s better to include:

- Prompts,

- Clear roles, and

- Checklists.

These pointers are guideposts that can help organizations tackle different kinds of crises.

💡 Pumble Pro Tip

Businesses of all sizes use crisis communication plans to preserve their reputation and operations. To find helpful crisis communication plan templates and see which one suits your organization, check out this exhaustive resource:

#4: Offering crisis communication and management training

Much of the responsibility for clear communication during a crisis falls on the shoulders of the emergency response staff. But, without instruction and established guidelines, they may not know how to proceed when unexpected issues arise.

For this reason, the staff should have access to annual training that will equip them to:

- Prepare ahead of time for turbulent periods,

- Grasp the importance of crisis communication management,

- Communicate with employees during a crisis,

- Answer questions and respond to criticism from both external and internal stakeholders, and

- Analyze past crisis response strategies and identify improvement areas.

In addition to HR staff and executives, this type of training should also involve public relations and marketing professionals.

Crisis communication in public relations is a powerful tool that can prevent the public from turning on a brand or organization. What might start off as an internal crisis can quickly spill over into the public sphere, so it’s essential to involve PR staff from the beginning.

Crisis communications: Best practices

Now that we’ve laid down the basic strategies, we can examine additional practices that will build a healthy foundation for crisis communication.

These actions and principles span all stages of crisis management, from preparing for a potential crisis to reflecting on it.

#1: Avoid silence

Organizations need to address the crisis as soon as it emerges. Even if the situation isn’t clear yet and we don’t have all the facts, we should communicate that we’re aware of the problem and gathering information. Silence indicates passivity and opens up space for others to control the narrative.

Furthermore, employees will expect relevant information from the organization and notice the lack of communication.

Failing to respond to an ongoing crisis will hurt the organization’s reputation among its stakeholders, including the employees.

#2: Don’t censor

While there’s disagreement on whether organizations should allow their employees to communicate with the media during a crisis, it’s usually futile to prevent employees from addressing the crisis with their private networks (both physical and virtual).

Rather than attempting to moderate or censor employee communication, companies should provide accurate information and relevant messages to enable them to discuss the crisis adequately.

#3: Stick to the facts

Crises are a time of uncertainty, and communication efforts should clear the way rather than exacerbate the issue. When communicating with employees and the public, organizations should stick with verified facts and avoid ambiguity and speculation.

Aside from potentially having significant consequences for those affected by the crisis, inaccuracy damages an organization’s credibility, which can have a far-reaching impact on the employees.

#4: Be consistent

It’s imperative that the messages an organization shares during a crisis are consistent in tone and content.

Inconsistency breeds confusion and creates an impression of incompetence.

Organizations need to ensure the necessary degree of coordination between different communicators so that they all have the same information and are aligned on the message.

#5: Show support

Employees caught up in an organizational crisis will likely be confused and concerned about their future.

Thus, companies need to:

- Identify and understand employee concerns,

- Show compassion,

- Create a psychologically safe environment, and

- Provide support through the process.

Crises find employees in their most delicate state, which makes it all the more important for organizations to adopt an empathetic approach when addressing employee concerns.

#6: Enable feedback

As we’ve already established, the key objective of internal crisis communication is restoring organizational trust.

Trustful relationships rely on two-way communication, and this does not simply stop in a crisis.

Organizations should implement open communication channels for feedback, allowing employees to:

- Voice their concerns,

- Ask questions,

- Comment on the process, and

- Provide suggestions.

Furthermore, companies should actively seek feedback through anonymous polls and other safe channels that allow employees to speak frankly without fear of retribution.

💡 Pumble Pro Tip

To learn how to use communication channels to facilitate feedback and improve engagement, check out this guide:

#7: Reflect

As vital as it is to have a plan, it’s just as crucial to analyze its effectiveness and execution.

Once a crisis has passed, organizations need to:

- Take a good look at their response,

- Identify what has worked and what hasn’t, and then

- Try to develop improvements.

Assessment of the success of a crisis communication plan should include employee feedback — evaluating their degree of satisfaction with various aspects of the communication.

What are the stages of crisis communication?

Timothy Coombs identifies 3 distinct phases of crisis communication:

- The pre-crisis phase,

- The crisis response phase, and

- Post-crisis communication.

Each stage carries distinct demands for collecting and interpreting information and then distributing that knowledge, so it’s important to examine them separately.

Stage #1: Pre-crisis phase

The fact that a crisis hasn’t occurred yet doesn’t prevent organizations from planning and preparing for that eventuality.

The activities in the pre-crisis phase focus on two areas — prevention and preparation.

Prevention of potential crisis

The prevention of a potential crisis is reflected in the attempts to reduce risks by identifying emerging developments and issues that could escalate into a crisis.

Early identification of such issues allows organizations to analyze and strategize their response.

In terms of communication, the detection of potential crises allows organizations to communicate the risks with the stakeholders, thus preparing them for worst-case scenarios and demonstrating a sense of control and competence.

Preparing for a potential crisis

Preparing for a potential crisis can only go to a certain extent, due to the unpredictable nature of many situations. This means that organizations can only identify and plan for a limited number of specific scenarios.

However, planning and preparation don’t need to be related to concrete scenarios.

There are many general steps and actions that organizations can take to prepare to respond to a potential crisis.

When choosing a more flexible planning approach, here are the steps organizations could take:

- Form a response team,

- Designate a spokesperson,

- Ensure effective communication among employees (by using internal communication software, for example),

- Formulate procedures and guidelines, and

- Provide specific training (communication skills, crisis management, etc.) for relevant individuals.

Stage #2: Crisis response phase

In this stage, a crisis impacting an organization is already unfolding, and the business has to respond to the events.

For organizations responding to crises, there are 3 universally accepted principles of crisis communication:

- Be quick,

- Be accurate, and

- Be consistent.

The above principles apply to internal crisis communication. When navigating public crises, we encounter a fourth principle — avoid saying “no comment.”

Author David Sturges, in the article Communicating through Crisis, suggests that perhaps even more important than how we communicate is what we communicate throughout the lifecycle of a crisis.

Sturges defines 3 focal points based on the strategic focus of the communicated content.

These are:

- Instructing information,

- Adjusting information, and

- Internalizing information.

Instructing information

Sturges states that the safety of those affected is the top priority in a crisis.

To protect themselves, organizations must shield their stakeholders. Otherwise, they will face an additional crisis by showing a lack of care.

Instructing information informs the people impacted by the crisis — in most cases, employees — how they should act. This type of information lets employees know how to protect their physical well-being and how to navigate the crisis at hand.

According to Sturges, instructing information should be distributed first as soon as the crisis emerges and the response team has enough situational awareness to formulate its message. Above all, instructing information should be:

- Accurate,

- Precise,

- Clear, and

- Actionable.

Adjusting information

As the crisis continues and its immediate effects subside, the focus of communication can shift from addressing the crisis itself to addressing its implications.

In essence, adjusting information informs people how to cope with the crisis psychologically.

This type of communication usually involves expressions of sympathy and announcements of any corrective actions to prevent the crisis from reoccurring.

Internalizing information

With the priority of the physical and mental well-being of the stakeholders already addressed, organizations can begin to protect and rebuild their reputations.

We use internalizing information to formulate our subjective image of an organization.

As there are countless strategies and approaches to reputation management, we won’t go further into the specific contents of internalizing information.

However, in the context of internal communication, internalizing information aims to restore and reinforce stability and the trust of employees in the organization.

Stage #3: Post-crisis communication

Communication should not cease once a crisis is considered resolved, as its consequences can linger long after its conclusion.

Post-crisis communication represents an extension of previous communication activities coupled with the lessons learned from the crisis.

Its primary aim is to manage the reactions of different stakeholders.

As an organization exits the period of crisis and attempts to revert to its usual operations, employees will want to know the following:

- When things will go back to normal,

- What this normalcy will look like,

- How the crisis has impacted the organization, and

- What steps the organization will take to prevent the crisis from happening again.

Why is crisis communication important?

Crises are disruptive events that sow:

- Fear,

- Confusion, and

- Uncertainty.

When a crisis emerges, the organization’s goal is to:

- Regain balance and stability and

- Ensure the continuation of its operations.

It’s impossible to achieve these objectives without the active participation of the entire staff.

Organizations must ensure that their members are safe and informed to achieve continuity in a crisis. Quality communication is imperative for this process.

Organizations need to communicate in order to:

- Inform their personnel,

- Allay fears, and

- Provide guidance on how to proceed forward.

Conversely, a lack of communication will only increase the uncertainty and create room for rumors to spread.

Furthermore, in today’s interconnected world, every employee serves as a spokesperson for an organization.

Effective internal communication during a crisis can be the key factor in employees publicly expressing negative or positive attitudes about the organization.

💡 Pumble Pro Tip

We’ve discussed the importance of internal communication for businesses during a crisis, but if you’d like to learn more about internal communication planning, you can head to this resource:

What are the common types of crises in the workplace?

While the specifics of a crisis are impossible to know in advance, organizations can still prepare for several common scenarios.

There are many ways we can categorize crises, but we’ll go with the division provided by Boston University professor Otto Lerbinger in his influential work The Crisis Manager: Facing Risk and Responsibility.

According to Lerbinger, these are the 7 types of crises:

- Natural crises,

- Technological crises,

- Confrontation crises,

- Crises of malevolence,

- Crises of organizational misdeeds,

- Workplace violence crises, and

- Man-made disasters.

#1: Natural crises

Natural crises are caused by natural elements, such as:

- Earthquakes,

- Floods,

- Tidal waves, and

- Epidemics.

Such occurrences can cause significant damage and present various challenges for organizations, including:

- Human and material losses,

- Operational difficulties, and

- Market disruptions.

Aside from their timing and severity, natural crises are generally predictable. Hence, organizations can prepare and implement contingency plans and procedures.

The contingency plans should include emergency notification and communication plans to reach all employees in time.

Example: The COVID-19 pandemic

We need to look no further than the recent example of the COVID-19 pandemic. This natural occurrence caused a global crisis impacting virtually all organizations.

Many businesses had to turn to hybrid and remote work to continue their operations, dramatically altering how we collaborate and communicate.

#2: Technological crises

Technological crises are possibly the most common crises organizations face today.

They are caused by the human application of science and technology and involve a broad scope of technology failures — from industrial accidents to software and hardware malfunctions causing disruptions in operations and services.

They can be harmful not only to a company’s operations but also to its reputation.

Example: The Deepwater Horizon oil spill

The British Petrol’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig explosion took place on April 10, 2010.

It claimed 11 lives and caused an oil spillage 1 mile below the ocean surface, which lasted for 87 days — releasing more than 4 million barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico.

It’s considered the worst environmental disaster in US history and one of the worst examples of crisis communication ever.

#3: Confrontation crises

Confrontation crises are intentionally provoked by individuals or groups to gain acceptance of their demands and expectations.

These individuals or groups can be:

- Members of the general public,

- Protesters,

- Activists, or

- Employees.

To cause a crisis, said groups and individuals use tactics such as boycotting or blockades, attempting to involve the media and the general public to draw attention to what they perceive as an organization’s negative activities or aspects.

Example: The Netflix walk-outs

Netflix found itself between a rock and a hard place in late 2021 when a group of employees organized walk-outs and joined protests over what they perceived as transphobic comments in a Netflix comedy special of actor and comedian Dave Chappelle.

Netflix’s response to the crisis (including publicized internal memos) drew much public criticism and even led to a campaign to cancel Netflix subscriptions.

#4: Crises of malevolence

This type of crisis incorporates a broad range of malevolent or hostile acts aimed at an organization.

Typical examples of malevolent acts are:

- Industrial espionage,

- Product tampering,

- Sabotage,

- Corporate terrorism,

- Cyberterrorism, and

- Other forms of foul play.

Example: The Chicago Tylenol poisonings

In 1982, 7 residents of the Chicago area died from poisoning.

An unidentified individual had tampered with packages of Tylenol (a common pain relief medicine produced by Johnson & Johnson), injecting them with cyanide and then resealing the packages and returning them to pharmacy shelves.

Johnson & Johnson decided to pull all packages of Tylenol from the market and only made the medicine available once they changed the sealing technology to prevent tampering.

#5: Crises of organizational misdeeds

Organizational misdeeds represent a broad range of management failures resulting in harm or risk for different stakeholders.

Crises caused by organizational failures tend to fall within 3 categories:

- Crises of misplaced management values: Leadership or management places short-term financial benefits above societal responsibilities, exemplified by actions such as cutting corners, neglecting safety, ignoring regulations, or downplaying risks.

- Crises of deception: These crises involve deliberate acts of concealment or deception, such as withholding evidence or lying about potential risks related to the organization’s products or services.

- Crises of management misconduct: These types of crises encompass acts of deliberate amorality or criminal activity, such as fraud, cheating, embezzlement, bribery, etc.

Example: The Volkswagen emissions scandal

In 2015, Volkswagen was found to be in violation of the US Clean Air Act.

US regulators determined that the German auto manufacturer deliberately tampered with the emissions software in some of its vehicles.

As a result, the emissions of the vehicles appeared to be up to 40 times lower than their actual emissions. Aside from a severely damaged reputation, the company spent more than $20 billion on fines, repairs, and compensations — with lawsuits filed both in the US and Europe.

#6: Workplace violence crisis

This type of crisis is caused by:

- Acts of violence,

- Harassment, and

- Discrimination by current or former employees towards other workers within the organizational framework.

As we can see, workplace violence refers not only to physical violence but also to harassment and other forms of employee mistreatment.

Example: The Activision Blizzard lawsuit

In July 2021, California’s Department of Fair Employment filed a lawsuit against Activision Blizzard, a prominent video game development company.

The lawsuit contained many accusations of sexual misconduct and discriminatory practices against women.

The fallout led to multiple upper management resignations and a substantial drop in market value.

Furthermore, the company’s internal and external response to the crisis resulted in employee unrest, which will likely take years to repair.

#7: Man-made disasters

This type of crisis refers to various catastrophic events caused by human actions.

Examples include:

- Terrorist attacks,

- Wars,

- Large-scale financial crises, and

- Other events disruptive to organizations and markets.

Example: The global financial crisis of 2007–2008

Years of questionable practices from a global web of financial institutions reached a catastrophic conclusion throughout 2007 and 2008.

The resulting global recession was considered the worst since the Great Depression, with countless businesses across the globe ceasing their operations or experiencing great difficulties.

Enhance internal crisis communication and management with Pumble

The importance of effective internal communication grows in times of crisis. Due to the disruptive nature of a crisis, employees will be desperate for:

- Information,

- Guidance, and

- Support.

Even before they are affected by a crisis, organizations need to implement preventative mechanisms and designate key personnel for such an eventuality.

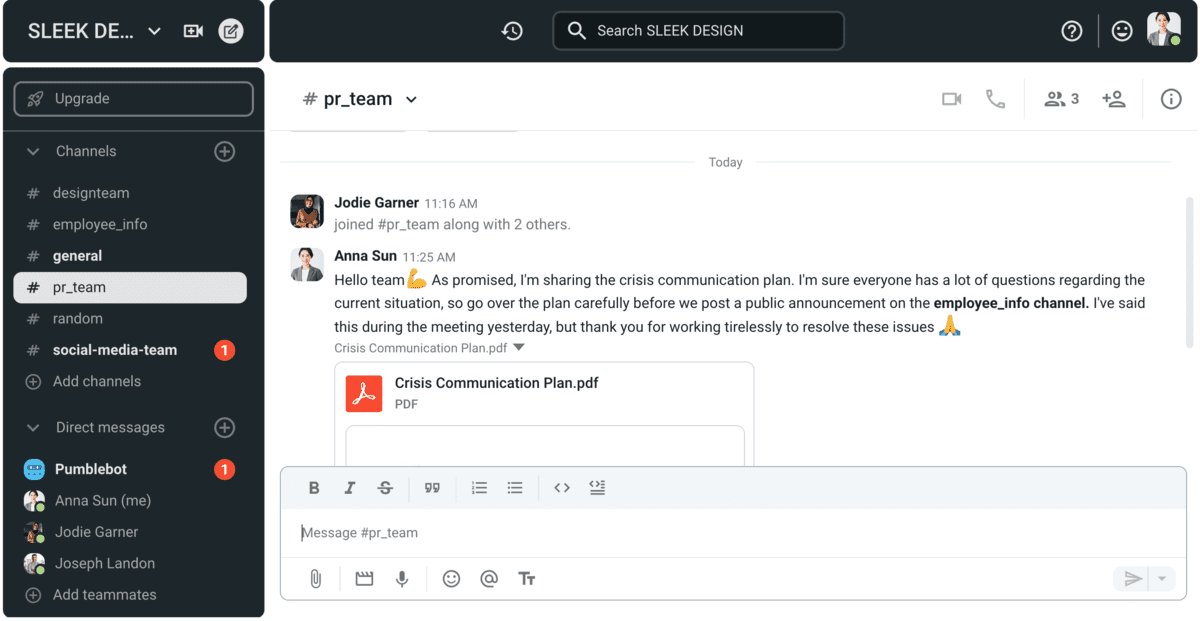

Most importantly, businesses should rely on easy-to-use communication software like Pumble to facilitate real-time communication and provide everyone with the necessary information.

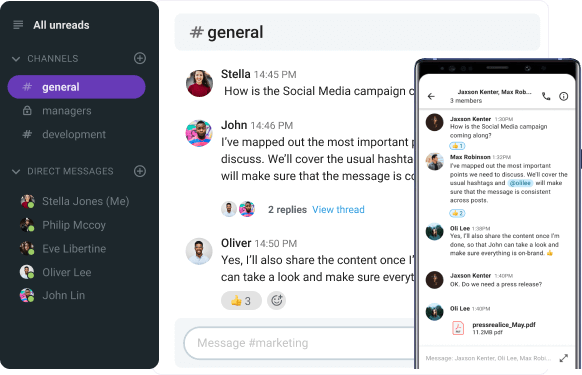

Pumble simplifies sharing information through:

- Public and private channels,

- Direct messages, and

- Threads.

You can use channels to post company-wide announcements, but if you want only to talk to specific employees or stakeholders, you can take advantage of:

- Video conferencing,

- Audio calls, and

- Voice and video messages.

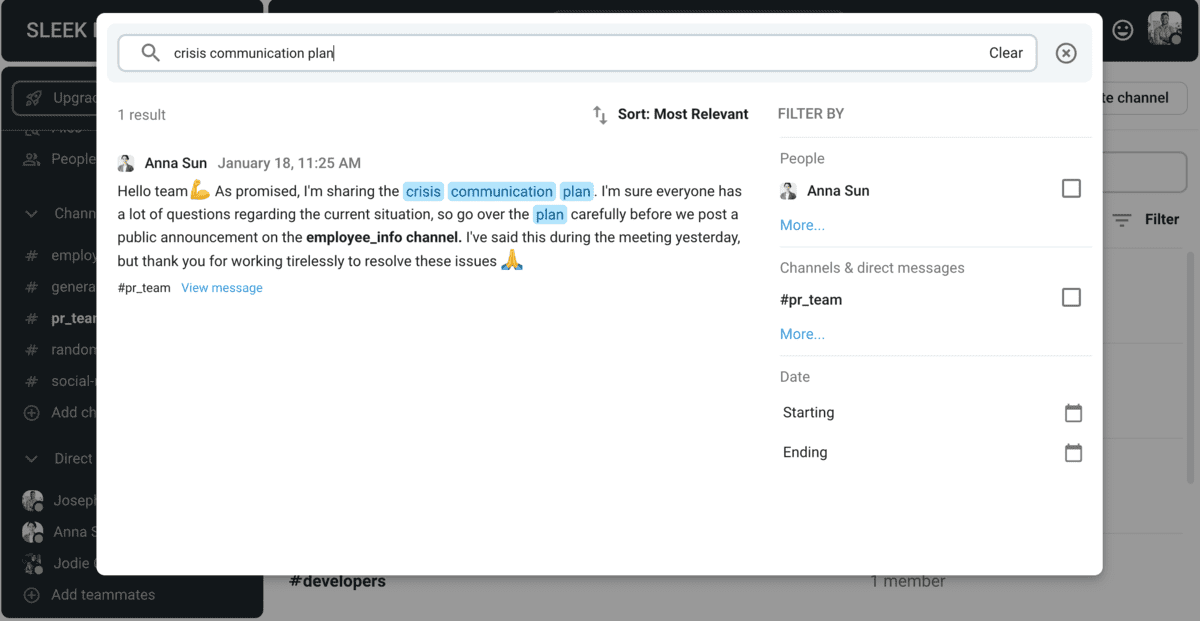

And, should your organization face a public or private crisis, you don’t have to worry about losing any documents or information. Thanks to Pumble’s Search feature, you’ll be able to find what you need by:

- Retrieving older files and

- Going through past conversations.

Benjamin Franklin stated, “By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail,” and he was right.

So, if you think Pumble can help your business bolster internal communication, create a free account today and see the benefits it may bring to your team!